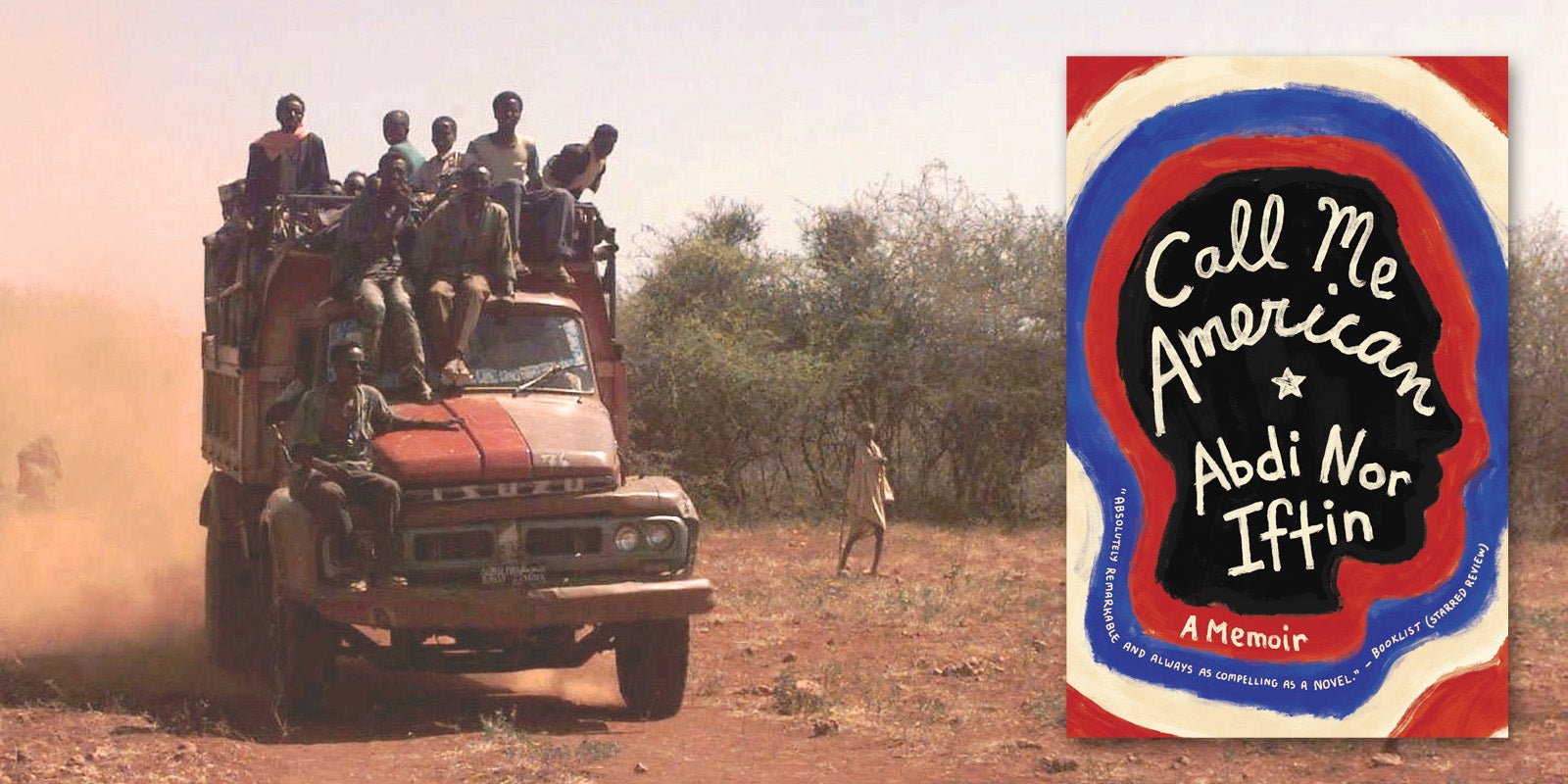

Introduced to American movies and pop music while growing up in Somalia, Abdi Nor Iftin fell in love with the idea of America long before he could find the country on a map. As the Somali Civil War broke out, Abdi grew desensitized to the violence around him: avoiding gunfire during his daily trip to get water for his family quickly became normalized. He dreamed of traveling to America, hoping for the day when he might find a way out and make it to the land of action heroes like Arnold Schwarzenegger.

In the following excerpt from Call Me American, Abdi describes the day that American troops arrived in Somalia to provide humanitarian aid during Operation Restore Hope.

By December of 1992, the world could no longer sit back and watch the starvation in Somalia. Humanitarian aid had been coming in for months but the warlords grabbed all the food and medicine for themselves and gave none to the people. The situation got worse until finally the United Nations decided to take action. Led by the U.S., twenty-eight countries organized a military task force called Operation Restore Hope. The goal was to supervise the distribution of food and supplies.

In Somalia we call Americans Mareekan. When I heard these Mareekan were coming to Mogadishu, I asked my mom who they were. I didn’t know the people in the action movies were Mareekan. “They are huge, strong, white people,” she said. “They eat pork, drink wine, and have dogs in their houses.”

This sounded like the people I had seen in the movies. Whoever they were, the militias looked worried about their arrival. Many rebels started burying their guns; some fled Mogadishu. There was confusion and tension everywhere. I couldn’t wait to see Mareekans land in Mogadishu! Hopefully they would look like actors in the movies and would spray bullets all over the militias.

“Through the bullet holes in our roof I could see the gleaming lights of the planes, accompanied by the roar of tanks along the roads.”

And so at midnight on December 9, the thunderous roar of Cobra helicopters and AC-130 gunships filled the air. From the ocean came the buzz of hovercrafts, unloading tanks and Marines onto the beach. Our house was close to the airport and the sea, so all these sounds woke me up right away. Through the bullet holes in our roof I could see the gleaming lights of the planes, accompanied by the roar of tanks along the roads. My mother, Hassan and Khadija were all up, even Nima.

I was eager to see the troops and the helicopters in the morning. At dawn Hassan and I, holding hands, walked down to the airport past streets that used to have sniper nests. There were lots of Somalis in the street, all of them headed the same way, towards the airport. As we got closer, the sounds of the Cobra attack helicopters became deafening. We joined a group of other excited Somalis, some standing on the walls, others on top of roofs, watching as big Chinook heavy-lift copters took off and landed. We could see warships in the distance on the blue ocean; everywhere around the airport, Marines in camouflage were taking positions and setting up gun posts.

Someone said the Mareekans had rounded up the rebels who were controlling the airport and seaport. The crowd got bigger and bigger, we shouted, laughed and cheered in excitement. Security perimeters had already set up, blocking entrances to the airport. The Mareekan flag was waving, stars and stripes. That’s when it hit me: I had seen that flag in movies! These Mareekans were the movie people, and this was a real movie happening in front of us!

Commando must be here, I thought. This is it. This is the moment I had been waiting for, to meet Commando and watch him blow away all the militias! Helicopters dropped a shower of leaflets with photos and information about the troops. I picked up several of them. “United Nations forces are here to assist in the international relief effort for the Somali people,” it said in Somali. “We are prepared to use force to protect the relief operation and our soldiers. We will not allow interference with food distribution or with our activities. We are here to help you.” Because not so many Somalis could read, the leaflets also showed an illustration like a comic book of a U.S. soldier shaking hands with a Somali man under a palm tree, as a helicopter flew past. I couldn’t wait to shake hands with Commando.

Everything was moving so quickly—the tanks, the soldiers, the planes. We jostled for positions to watch the movie that was happening in front of us. Except there was no gunfire. I kept waiting for the battle to start, I wanted the Chinooks and Cobras to blast away at the rebels. But everything was peaceful. Then I remembered it’s always like this in the movies. First you see all the heavy machines and helicopters gearing up for action, then the battle comes later. I wanted to see the militias face these troops, but the rebels I had known since we returned to Mogadishu were now walking around unarmed, acting like regular people. They didn’t dare to face Commando.

“For the first time my friends, my brother and I could go out on the dusty streets after dark and play games, laugh and talk.”

I watched all day as the Marines took positions, more and more of them coming. Two men in uniform waved to let us cross the airport runway up to the sand dunes, so we could watch as the hovercrafts brought more and more Marines from the sea. Humvees and tanks roamed noisily but never fired a shot. I was getting impatient for the battle to start. We watched as the troops pulled out their stuck Humvees from the sand dunes. Hassan and I grew bolder and edged close to the troops. I stood there with my mouth open, watching them drink from a water bottle and smile at us. I made a sign asking for water, and the white guy in uniform went into the Humvee and handed me a plastic bottle. Then we made eating signs with our hands to our mouths, and they handed us tasty marmalade, bread and butter. The Commando lookalikes even spoke to us in Somali, but all they could say was “Somali Siko!” Somali move back.

One of the Marines threw a chocolate candy to me. I grabbed it and swallowed the whole thing. When I got home and told Mom, she gave me a hard slap.

“You must not eat pork!” she said.

I told her I didn’t think it was pork, it was sweet, but she didn’t believe me. How would she know what pork tastes like?

Night came again, and Mogadishu was noisier than I had ever heard it. But for the first time in two years, there was no sound of explosions and gunfire. We were surprised how the Marines lit up the airport. Lights came from everywhere, helicopters, tents, cars. It looked like daytime in the middle of the night. We were not allowed to get too close to the airport at night—“Somali Siko!” the Marines yelled over and over. But for the first time my friends, my brother and I could go out on the dusty streets after dark and play games, laugh and talk. We counted the helicopters as they flew over, and the big gunships that circled over the city. Falis’s movie theater could now stay open at night, but we did not go. For the first time in years, outside was even more exciting than the movies.

Copyright © 2018 by Abdi Nor Iftin. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Learn more about Call Me American by clicking the link below: