The Georgia Center for the Book, an affiliate Center of the National Center for the Book in the Library of Congress, has released the list of Books All Georgians and Young Georgians Should Read 2024. All books are selected works with Georgia connections—either by prize-winning authors and illustrators from Georgia or about topics important to Georgia. 2024 marks the eleventh annual release of the reading list.

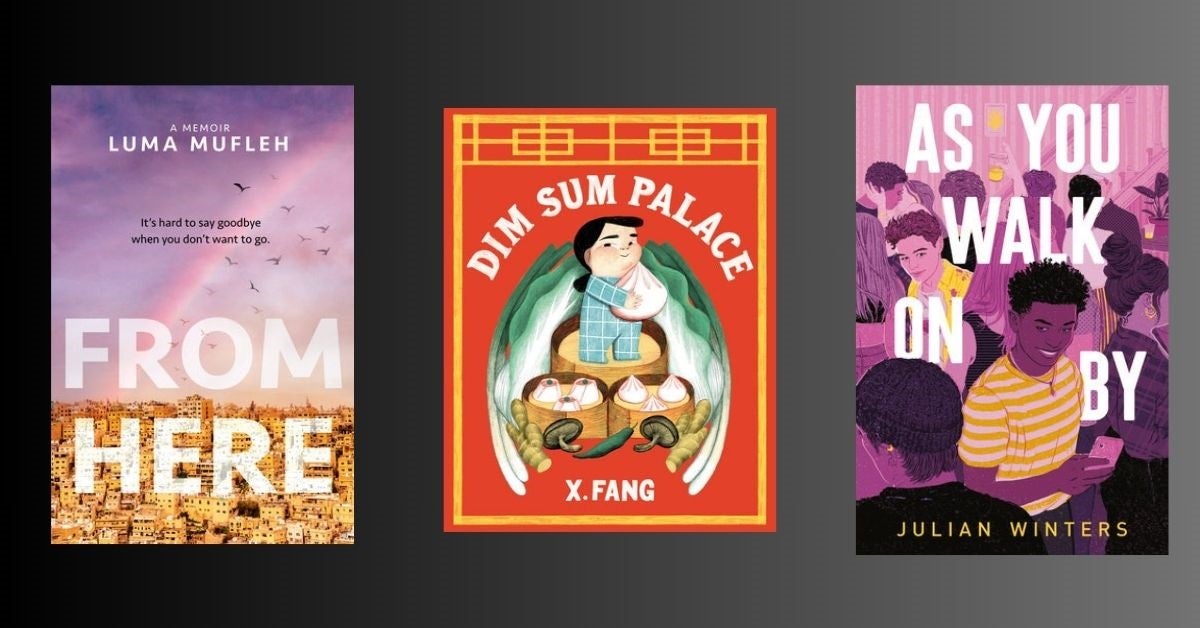

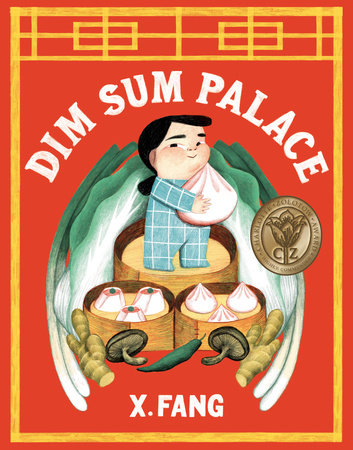

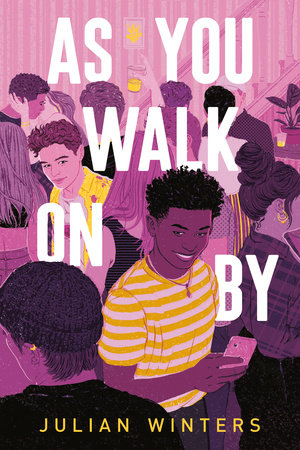

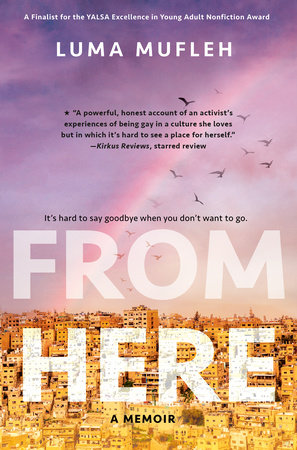

The list includes three Penguin Random House titles: Dim Sum Palace by X. Fang (Tundra), As You Walk On By by Julian Winters (Viking Books for Young Readers), and From Here by Luma Mufleh (Nancy Paulsen Books).

Learn more about each title below and explore the full list here.