from the Introduction by John Phillip Santos

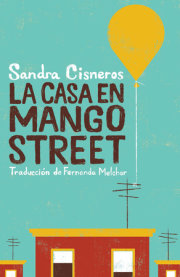

When we meet Esperanza Cordero, the almost mystically knowing young Chicana narrator of The House on Mango Street, she is already very much a canny teller of tales, speaking in medias res, in the midst of an unfolding story of her heroic quest to find a true home.

“We didn’t always live on Mango Street,” she begins. She details a litany of her family’s peregrinajes through previous houses in Chicago, as if reading from some codex memorializing a series of sacred migrations: “Before that we lived on Loomis on the third floor, and before that we lived on Keeler. Before Keeler it was Paulina, and before that I can’t remember. But what I remember is moving a lot. Each time it seemed there’d be one more of us. By the time we got to Mango Street we were six – Mama, Papa, Carlos, Kiki, my sister Nenny and me.”

Involuntary peregrinations and deprivations spark Esperanza’s imagination. Her family has had to leave their previous residence when the “water pipes broke and the landlord wouldn’t fi x them because the house was too old. We had to leave fast.” Esperanza dreams of a house with “running water and pipes that worked.” She imagines a house with “three washrooms so when we took a bath we wouldn’t have to tell everybody.” It would be a white house, surrounded by a proper yard with trees and grass. “This was the house Papa talked about when he held a lottery ticket and this was the house Mama dreamed up in the stories she told us before we went to bed.”

But as Esperanza candidly reveals, the family’s new house on Mango Street only has one bathroom, and “Everybody has to share a bedroom – Mama and Papa, Carlos and Kiki, me and Nenny.”

“I knew then I had to have a house. A real house. One I could point to. But this isn’t it. The house on Mango Street isn’t it.” And then, fathoming her disappointment and longing, Esperanza takes us into her confidence, she shares something that is beyond an intuition – it’s a glimpse at a secret, deeper knowing of unknown origin that will propel and inflect the unforgettable stories that are to come: “For the time being, Mama says. Temporary, says Papa. But I know how those things go.”

How can she know this? How can such she already know the way things go? And why is she offering us her testimonio?

It’s Esperanza’s ineluctable knowing and her indelible way of expressing it which transfi xes readers around the globe with a universal human story of a young girl’s becoming, establishing

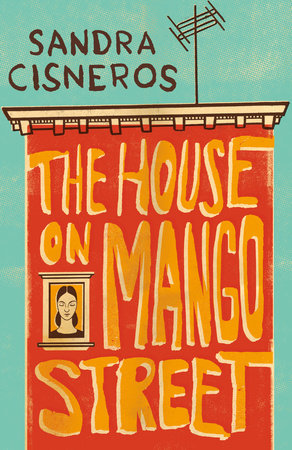

The House on Mango Street over decades as the first Latinx American classic of world letters. Seven million copies have been sold in the United States, and millions more abroad, in as many as twenty-six translations. Notably, it is also the fi rst book by a US-born Latinx writer to be included in the legendary and august Everyman’s Library series, auspicious indeed for the author and the book – as well as for the series. And as celebrated as the novel has been in the forty years since its publication, it’s important to point out that despite wide adoption in school curricula, it has also been banned from schools in numerous fl ashpoints during America’s recent and ongoing culture wars, officially cited for “age appropriateness” – but it’s Esperanza’s searing powers of observation, and her “knowing” of the world around her, especially coming from a young Chicana, that seem to strike fear in some people’s hearts.

As the author of

The House on Mango Street, Sandra Cisneros brings a profound new embrace of a unique literary legacy of the Americas to the Everyman series, as an American writer who is mestiza, feminista, urbana, cosmopolitana, and sin vergüenza – all without shame.

Esperanza’s limpid voice, her deceptively simple diction, her unique lyrical vernacular, belie a profound understanding of the complex intricacies of our humanity that can’t be fully explained, but it has deep roots in the experiences, readings, and understandings of the author, herself an oracle of a knowing that eludes explanation.

*

I met Sandra Cisneros in my hometown of San Antonio, Texas in 1983, just before the publication of

The House on Mango Street by a small Latino publishing house in Houston, Arte Público Press, that first published works of now well-known Latinx writers, as well as “lost” Latinx literary works. Vivacious, loquacious, and audacious, with an electric halo of ebony curls, she was by then entirely a protean whirlwind of literary marvel. She was just back from a walkabout across Europe (including four months in Yugoslavia), and the Mediterranean. Both of us were aspiring writers, but her aspirations were feverishly inquisitive, passionate and opinionated, volubly rooted in a commitment to writing as an act of bounding invention, and social conscience. A poet and fiction writer, she possessed a documentary eye that saw the many ways the world oppressed the poor and the marginalized.

She was a force unlike any I’d yet encountered, determined to use her gifts to sow new seeds in the fallow fi elds of American letters, so long ignorant and dismissive of voices like hers. And Chicanx letters, the work of Mexican American writers, were in an uncertain, in-between moment, emerging from a rich movimiento history into we-knew-not-yet what was to come.

As fate would have it, we were the finalists to become the inaugural Director of the literature program at the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, a newly created haven for Mexican American arts, literature, music, and theater in my hometown of San Antonio. Sandra (forgive the familiarity, but to refer to her any other way feels fake) got the job, but in meeting her then, I gained a lifelong literary ally, interlocutor, mentor, and occasional conspirator.

I had learned much from powerful women writers. I grew up with the poet Naomi Shihab Nye, had carried on a fraught correspondence with Laura (Riding) Jackson, and now Sandra arrived in San Antonio with a spell-binding sense of her own destiny, a destiny that would shortly unfold further in grand ways that were somehow against all odds while possessing a certain inevitability. She was an inspiration, and indeed, in three-hundred-year-old San Antonio she would eventually become La Sandra, a transforming presence for the city, and eventually for American literature.

It would take a while yet for the world to fully take note of

The House on Mango Street, the mesmerizing testimonio of the journey of Esperanza Cordero among the souls and spaces of her Chicago neighborhood, as she struggles to assert her place in the world, as she longs for the dreamed-of house of her own. The path of this now universally classic novel to this Everyman’s Library edition would be lengthy, and bumpy.

After the book’s initial publication by the Houston small press, Sandra met her agent and forever since dharma companion Susan Bergholz. It was with the eventual publication of The House on Mango Street by Vintage Books in 1989 that the novel would begin to find its staggering, first national, then ever-widening global readership. But that wasn’t thanks to any career-forging reviews in major newspapers or literary journals, virtually all of whom maintained their studied inattention and ignored the book. I remember it more as a gradually rising tide of word-of-mouth revelations, people passing the book along to one another like the talisman of a new reckoning with ourselves.

Like my thirteen-year-old daughter Francesca, who recently read the copy I handed her for the first time, after which she shared: “As a young Latina who is still figuring out everything, this book gave me so many ways to relate to the young protagonist. I saw myself in her, and I think many other girls my age could too. The feeling of not wanting to be contained – to not be limited to the things we get to do, say, or experience. The longing for more is something I cannot only greatly appreciate, but also deeply understand. I loved this book because usually when adults try to get into the minds of children, it’s a colossal fail. It’s unrealistic – and can even feel like they’re mocking us. It just doesn’t sit right. Sandra goes into the minds of children in a realistic way, adding beautiful touches of vibrant culture that makes me proud to be a Mexican American.”

You get it? Literally millions have shared this experience, and this is a book that continues to light up souls.

Copyright © 2024 by Sandra Cisneros; Introduction by John Phillip Santos. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.