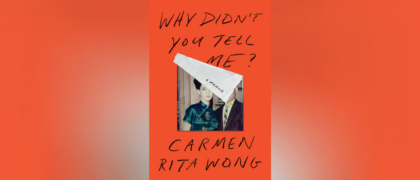

Chapter 1

. . . Because the Stage Was SetOne of my first memories is being dolled up one night in a miniature rabbit-fur chubby coat made by my abuela, my mother’s mother, whom we called “Mama.” She was an elegant, square-faced, handsome Dominican woman who kept her deep-black straight hair in a short, chic cut, never leaving the house without red lipstick. She worked in Midtown Manhattan as a seamstress for Oscar de la Renta, the suave, perpetually tan Dominican American fashion designer with a legacy of dressing First Ladies starting with Jackie Kennedy, and who filled his workshops with immigrant women from his home country. Abuela dressed for work every day in a smart tailored navy or black Oscar skirt suit and a starched white or cream collared blouse. She was divine to me.

My chubby coat was calico in color and uneven. There were variations in the length of the fur pieces, all shades of brown, from light to dark, patchy like a calico cat. It was sewn of remnants from Mama’s salon, a manufacturing loft filled with her fellow countrywomen, who were most likely also various shades of brown and Black, speaking to the island’s history of enslavement and colonialism as old as Columbus’s first landing. I couldn’t have been more than three, almost four years old that night, but what I remember most was the feel of that fur, the absolute luxe of it, unspoiled by any knowledge of the carnage that happened to put it on my back. And I remember that in wearing the coat, along with my fancy lace-up go-go boots and emerald-green velvet evening purse—also custom-made for me with a rabbit’s fluffy gray tail smack in the middle at the clasp—I felt like the most loved and special thing. I remember it so well because it was a feeling that was rare and would be gone from my life all too soon.

I was dressed up to go out with my older brother, Alexander (“Alex” to everyone except our parents), to Chinatown with our father, Peter “Papi” Wong. He was coming to pick us up from our apartment in Morningside Heights, which at that time, the 1970s, was Harlem. My brother and I lived alone with our young mother, Lupe, a firstborn child in her father’s second family. My grandfather, Abuelo, had two families: one with his wife, who was somewhere else in New York City at the time, and one with his longtime—let’s call her partner: my grandmother, Mama. It was decades before I’d find out that this was typical of Dominican culture back then (and it’s handed down still a bit today), for a man to have a wife, never divorce, but have another family (or more) and even live with this other family, like my grandfather did. Of course, this was never spoken of, and I didn’t meet anyone from Abuelo’s other, “legitimate” family—our family—until nearly thirty years later.

“Ay, m’ija, que linda eres!” Abuela said to me as she bent down to put the hook into the eye at the top of my coat. She would say this phrase to me like a mantra, that night and every day that I was lucky enough to see her: Que linda. Her greeting to me was always this, and what I heard was, Oh, my child, how lovely you are. It could never have been said to me enough. But it wasn’t about my appearance. When Mama held my face in her hands, she looked into my being and told me, me, that I was worthwhile, even with all she could see inside me, just as I was and as all I was to be. No one before or since has done the same. But at three or four, the prime years in which we shape and form ourselves, our personalities and programming, that was all I needed to build a foundation for the adventure and struggle that was to be the rest of my life.

I hear my abuela’s voice so clearly in my memories, but I find it a bit strange that I don’t remember my mother’s voice at all before the age of maybe five or six. Her silence, or my perception of it, is a striking impression from my childhood. I can see her clearly, though. I saw my mother, “Mami,” Lupe, that night at the end of the narrow and dimly lit railroad apartment hallway, holding open the door for my brother and me. Both of us kids all gussied up and fresh and clean for a night out on the town with our Chinese father, who didn’t live with us. Papi and Mami were still married but separated. Abuela had kissed me on my cheek and turned me around to follow Alex down the hall to the door. My jaunty boots clip-clopped on the linoleum. Mami held the door open to Papi but didn’t let him in. He was a bit thin then, and small, maybe five foot five, looking like an Asian Johnny Cash, dressed all in black, a slick fitted jacket (more biker than suit), hair Brylcreemed back into a low, shiny black pompadour.

As Papi spoke, he embraced us each with one arm like we were buddies. He always did that. “Cah-MON! Cah-mon, there’s my daughter and here’s my son! My son. Okay, okay, let’s go. Ready to eat? You hungry?”

I’m sure we got to Chinatown, nine or ten miles downtown, by car, Papi’s preferred mode of transportation. Later I would find out why he always had a car or van. Let’s just say that it was job related. Our two closest cousins lived on the street that intersected ours in a building we could see from our windows. They also had a father not living with them who was Chinese. Un Chino. I remember that he had a car too, one we’d see parked in front of either their building or ours. No one in our Dominican family had a car, though.

The restaurant was overwhelming in size, filled with gold chairs as far as my eyes could see, and red, so much red, and people and chatter everywhere. Eyes were on us. When our father, Peter Wong, entered a space, no matter the expanse, he made sure you heard and saw him coming. Chinese Johnny Cash was a star, you see, in his mind. And he was being followed by his two darker, not very Asian-looking children. But two children who looked very much like each other, big brown eyes, tan-colored skin, black curly hair, though my brother carried a hint of the Asian fold in his eyelids that would grow more pronounced over time, along with enviably lush lashes. We were just two little brown kids who looked like full siblings, Black, white, and gold.

“Aaaaa!” Peter greeted every server, host, male person, standing or not, that he passed. He rattled off in whichever dialect was applicable to whomever he was addressing. Papi was Taiwanese born, of Chinese descent, a former merchant marine who worked as a chef on a Norwegian shipping vessel. One day he stepped off his ship as it docked at a pier in Manhattan, and never looked back. No bags, no belongings, no home or friends or family. You’d better believe that this slick, car-owning-in-the-city man knew how to hustle his way around this town. Or at least this neighborhood. He had little formal education, yet he could speak English, simple Spanish, and multiple Asian dialects. He was also thirty-four years old to my mother’s nineteen when he married her, seven years before I was born. He had fourteen or more years in the United States to my mother’s four.

I wish I could tell you a loving story, a cross-cultural heart-filled fest of American melting-pot dreams, of how a teenage Dominican immigrant girl ended up married to a thirty-something Chinese immigrant man, but no. The story is instead in two extremely unromantic parts. One leads to the question of the cars, and one to racism.

White supremacy steeped in the history of the enslavement of African peoples is a thing not only in the United States but also in South and Latin America and the Caribbean, particularly in the Dominican Republic. This flavor of oppression meant that when you married off your daughters (and there was no marrying without your father’s permission or choice), especially in the “Ju-nited States,” you had to marry someone who elevated your racial status and therefore your family.

This was my mother’s answer to me when I asked her many years later: “Mom, why did Abuelo have both you and Maria [her sister] marry Chinese?”

Lupe: “Because the Chinese were the closest thing to a white man.”

“Oh . . .”

There was another (still racist) story of my grandfather that my mother floated around when she was being more obtuse about it all. She tied it to Abuelo’s business in Santiago, Dominican Republic, being next to a Chinese-owned business and “how well they managed the business. They were good people. So, that’s what he wanted.”

“Ah . . .”

Abuelo was also a Brylcreem man but his hair wasn’t straight and black like Papi’s or even Mama’s. It was a Langston Hughes finger wave, like a 1920s Harlem bandleader. He was a light-skinned Black man who stayed out of the sun and would most likely beat anyone who would dare to call him “negro”. In our home, in our Dominican community, we were “Spanish,” a common colonial misnomer in the seventies and beyond. Dominicans have a long and tragic history of racism and denial of their African ancestry. As with the United States, it has a colorist caste system that grew out of European conquest and rule. Ideas of anti-Blackness stuck with those who left the island to establish themselves into our Dominican–New York–immigrant–American life. So, even today you’ll hear old-school Dominicanos call themselves “Spanish.”

Copyright © 2022 by Carmen Rita Wong. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.