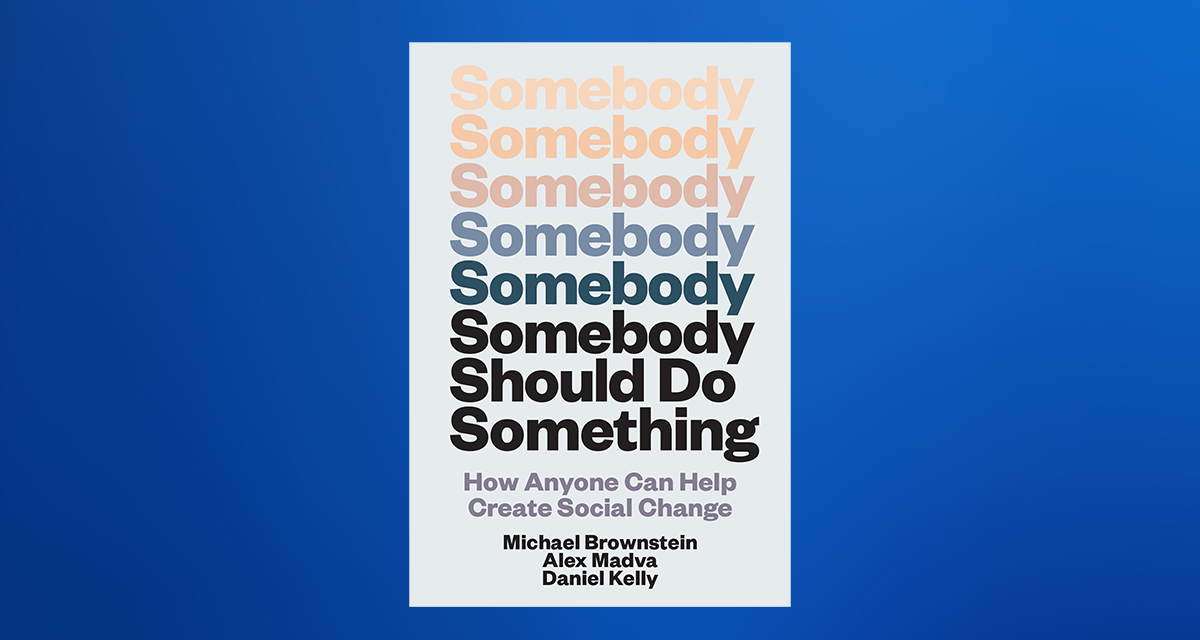

Changing the world is difficult. One reason is that the most important problems, like climate change, racism, and poverty, are structural. They emerge from our collective practices: laws, economies, history, culture, norms, and built environments. The dilemma is that there is no way to make structural change without individual people making different—more structure-facing—decisions. In Somebody Should Do Something, Michael Brownstein, Alex Madva, and Daniel Kelly show us how we can connect our personal choices to structural change and why individual choices matter, though not in the way people usually think.

The authors paint a new picture of how social change happens, arguing that our most powerful personal choices are those that springboard us into working together with others—warehouse worker Chris Smalls’s unionization at Amazon is one powerful example. Taking inspiration from the writer Bill McKibben, they stress how one “important thing an individual can do is be somewhat less of an individual.”

Organized into three main parts, the book first diagnoses the problem of “either/or” thinking about social change, which stems from the false choice of making better personal choices or changing the system. Then it offers a different way to think about social change, anchored in a new picture of human nature emerging across the social sciences. Finally, the authors explore ways of putting this picture into practice. Neither a how-to manual nor an activist’s guide, Somebody Should Do Something pairs stories with science (plus some jokes) to help readers recognize their own power, turning resignation about climate change and racial injustice into actions that transform the world.

The three of us spent a long time feeling stuck about what we could do about the biggest problems we collectively face, problems like climate change, racism, and yes, car culture. It seemed to us that we were being forced to choose between personal choices or systems and social structures.

This book is about getting unstuck. Our personal choices do matter, just not the way we usually think.

Part of why it’s hard to see this is that would-be changemakers are constantly told they have to choose: change people or change systems. “You can’t save the climate by going vegan,” a USA Today op-ed proclaimed in June 2019. “Corporate polluters must be held accountable.” This widely circulated essay argued that focusing on individual actions like what to eat and how to travel “distract from the systemic changes that are needed to avert this crisis.”

From our perspective, the authors are right that the climate crisis is only going to be solved with systemic change. They’re also right to be suspicious of putting the responsibility for change at the feet of individual consumers.

But the authors’ overall message falls short: They make what we shouldn’t do much clearer than what we should. “Don’t change lightbulbs,” they say, “change [the] energy system.” The first part of this message seems straightforward. Stop stressing over individual actions like how to light homes and stock fridges. Got it. But what to do instead? What can any of us do to hold corporate polluters accountable and overhaul energy infrastructure? The philosopher Robin Zheng put the crucial unasked question this way: “what is my role in changing the system?”

Lurking in the background of USA Today’s op-ed—and behind the dominant cultural conversation about social change—is the portrayal of people as isolated from each other, with limited reach, able to adjust a few things here and there in their own personal lives but not much else. It highlights divisions rather than connections, boundaries rather than pathways of influence. It underlines opposition: real-deal change is taking down the car companies or fossil fuel industry rather than making changes in your own life.

We need a better picture, one that highlights how personal choices are connected to systems and structural change. We need a picture that foregrounds our most powerful personal choice: to work together with others. As the writer Bill McKibben put it about climate change, “the most important thing an individual can do is be somewhat less of an individual, joined together with others in movements large enough to make those changes on [a] more fundamental level.”

We need images and models and stories that help us see what kinds of personal choices merely make us feel good but are basically ineffectual, and what kinds actually have the potential to create transformative social change. This book assembles these images and models and tells many of these stories. It offers them in service of getting unstuck.

Copyright © 2025 by Michael Brownstein, Alex Madva, and Daniel Kelly. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Michael Brownstein is Professor and Chair of Philosophy at John Jay College and Professor of Philosophy at The Graduate Center, CUNY. He is the author of The Implicit Mind.

Alex Madva is Professor of Philosophy, Director of the California Center for Ethics and Policy, and Co-Director of the Digital Humanities Consortium at Cal Poly Pomona. He is a coeditor of An Introduction to Implicit Bias and The Movement for Black Lives.

Daniel Kelly is Professor of Philosophy at Purdue University. He is the author of Yuck! The Nature and Moral Significance of Disgust (MIT Press).