What makes a good life? The question is inherent to the human condition, asked by people across generations, professions, and social classes, and addressed by all schools of philosophy and religions. This search for meaning, as Yale faculty Miroslav Volf, Matthew Croasmun, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz argue, is at the crux of a crisis that is facing Western culture, a crisis that, they propose, can be ameliorated by searching, in one’s own life, for the underlying truth.

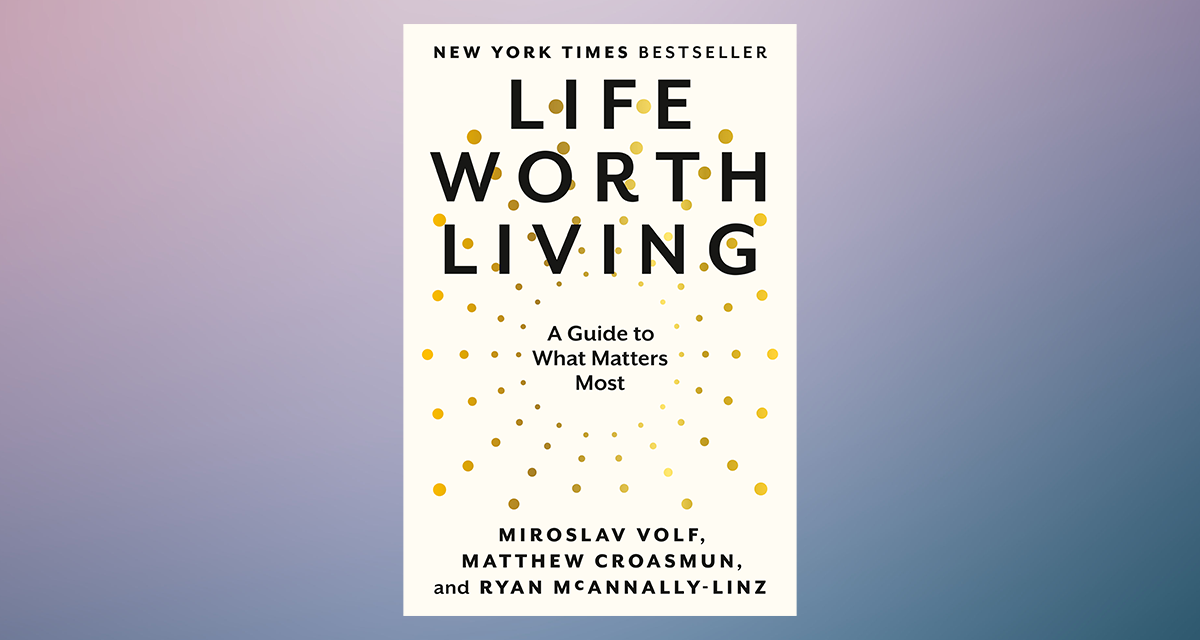

In Life Worth Living, named after its authors’ highly sought-after undergraduate course, Volf, Croasmun, and McAnnally-Linz chart out this question, providing readers with jumping-off points, road maps, and habits of reflection for figuring out where their lives hold meaning and where things need to change.

Drawing from the major world religions and from impressively truthful and courageous secular figures, Life Worth Living is a guide to life’s most pressing question, the one asked of all of us: How are we to live?

Introduction

This Book Might Wreck Your Life

Before he became the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama’s life was going quite well by the usual standards. He was a prince, after all, and enjoyed the luxuries and privileges of royalty. He lived in an opulent palace, ate delicacies, dressed in fine clothes. His father cared for him and was grooming him to rule the kingdom. He had married a princess. They were expecting their first child.

Wealth, power, and familial bliss were his. Every day, he tasted the fruit of the good life. Until it all turned to ashes in his mouth. One day, while riding through the royal park, Siddhartha saw a feeble old man and was struck by the tragic decay of age. The next day, in the same park, he came upon a sick man. And the day after that, a rotting corpse. Thoroughly shaken by the suffering that seemed to pervade existence, he returned once more to the park, on the day of his son’s birth. This time, he met a wandering monk and was overtaken by the impulse to renounce his royal life.

That very night, Siddhartha left everything to seek enlightenment. He didn’t stop to say goodbye to his wife and newborn son, for fear that his courage would fail. His life was now a quest. He had seen the truth of suffering and would not stop seeking until he had found the way to overcome it. He began to fast and to discipline his body, trying to attain release through spiritual exertion. All to no avail. So he searched elsewhere.

Several years after leaving home, Siddhartha sat motionless at the foot of a fig tree. For seven weeks he meditated, until at last he reached the insight he had been seeking: suffering comes from craving, so the one free from craving will be freed from suffering. He dedicated the rest of his life to communicating this insight, delivering the gift of enlightenment to anyone who would receive it. Nearly twenty-five hundred years later, his teachings shape the lives of millions of Buddhists and countless others who have found value in his way of life.

Before he became known as the first pope, Simon was an ordinary man. He lived in a small house in a small town by a small lake in a small fiefdom at the edge of a very large empire. He had married a woman from the same town and lived near his in-laws. Like many of his neighbors, he made his living as a fisherman. He spent many of his nights out on the lake with his brother, Andrew, plying their trade, looking for a catch. On the seventh day of the week, as the law of God commanded, he rested and attended services at the local synagogue.

A stable trade, a family, a community. Not a flashy life, but a respectable one filled with ordinary goodness. Until two words turned the whole thing upside down.

“Follow me.” Jesus, the new teacher from Nazareth, stood on the shore and called to Simon and Andrew. Ordinarily, this would be crazy talk. Who walks up to two guys at work and tells them to drop everything and follow him around? But Jesus spoke with surprising authority. Word around town was that his preaching rang true, that his words carried power, that amazing things happened when he was there.

For some unknown reason, Simon followed. For three years, he listened and tried to understand. Awestruck, he watched miracle after miracle. He learned to call this man not merely “teacher,” but “Lord.” And this lord, in turn, gave him a new name: Peter, which means “rock.” But time and again, Peter failed to live up to his name. He misunderstood, he got overzealous, and when it counted most, he lost his nerve: when the authorities arrested Jesus, Peter denied even knowing him. He watched helplessly as imperial soldiers crucified his Lord. Everything would have been lost, all of his following come to nothing. Except that on the third day, astonishingly, he encountered his Lord, raised from the dead.

From then on Peter’s whole life was devoted to living as Jesus directed and spreading the good news about him. For years, he led the growing community of followers. Not many fishermen got farther away from home than a hundred-mile pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Peter’s mission led him to Syria and Greece and even the imperial capital, Rome. Eventually, it led to his death. According to Christian tradition, Peter was crucified in Rome. He is said to have insisted that he be hung upside down, because he was not worthy of the honor of dying in the same way as his Lord.

Before she was the hero of the anti-lynching movement and an icon of Black and women’s liberation, Ida B. Wells was a young woman building a life in the midst of difficult circumstances. Born into slavery in Mississippi and freed as a child by the Emancipation Proclamation, Wells lost her parents and her infant brother to a yellow fever epidemic when she was sixteen. To support herself and her surviving siblings, she took a job as a schoolteacher. By her twenties, she had saved enough money to purchase a one-third share in an upstart newspaper, the Free Speech, and start a journalistic career. Things were looking up. Until a horrifying but all-too-predictable injustice changed everything.

On March 9, 1892, Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and William “Henry” Stewart were lynched just outside the Memphis city limits. The crime was personal for Wells: she was godmother to Moss’s daughter, Maurine.

The experience led Wells to see that she had been fed a lie: “Like many another person who had read of lynching in the South, I had accepted the idea meant to be conveyed—that although lynching was irregular and contrary to law and order, unreasoning anger over the terrible crime of rape led to the lynching; that perhaps the brute deserved death anyhow and the mob was justified in taking his life.” But Wells knew Moss and McDowell and Stewart. They “had committed no crime against white women.” Suddenly, she saw that lynching was really “an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.” Few others in her time would speak this truth so clearly.

When Wells said it plainly in print, “a committee of leading citizens” (i.e., a mob of White vigilantes) ransacked the offices of the Free Speech and left a note “saying that anyone trying to publish the paper again would be punished with death.” Wells lost her paper, but she stood firm in her vocation to tell the truth about lynching to a world that often didn’t want to listen.

She carefully researched lynchings throughout the United States and published her findings in widely circulated pamphlets. She spoke throughout the American North and in Britain. She influenced the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Wells also worked tirelessly for women’s rights, helping build the Alpha Suffrage Club and the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC). In 2020, Wells was posthumously honored with a Pulitzer Prize special citation. Millions have benefited from her tireless work and unfailing commitment to truth.

The Question

Gautama Buddha: the privileged prince who became the venerable founder of one of the world’s great traditions. Simon Peter: the fallible follower of Jesus who became the rock on which the Christian church was built. Ida B. Wells: the stable schoolteacher who became the truth-telling icon of Black and women’s liberation. Three very different people with very different lives. What their stories share is an experience that put the shape of their lives into question. What had been normal and assumed became questionable. Something—maybe everything—had to change.

Implicit in these experiences was a fundamental, hard-to-articulate question. There are countless ways to try to express it: What matters most? What is a good life? What is the shape of flourishing life? What kind of life is worthy of our humanity? What is true life? What is right and true and good?

None of these phrasings captures it completely. The question they try to articulate always exceeds them. It always escapes full definition. But that doesn’t make it any less real or any less important. Hard as it is to pin down, it is the Question of our lives. The Question is about worth, value, good and bad and evil, meaning, purpose, final aims and ends, beauty, truth, justice, what we owe one another, what the world is and who we are and how we live. It is about the success of our lives or their failure.

However it gets to us, when the Question comes, it threatens (or promises?) to reshape everything. Nothing was ever the same for Siddhartha after his renunciation or Simon after his call or Wells after she took up her vocation in response to the murder of her friends. From one perspective, their lives were wrecked. From their own new perspectives, however, their lives had been reoriented. True, they gave up a lot. (In Wells’s case, the loss was double. What she gave up came on top of what the lynch mob had taken from her.) But what they gained—transformation, a radically new orientation toward the world and their place in it, a driving impulse for their lives—was qualitatively more important. Indeed, it was more important to them than their very lives.

This book is about the Question.

We’re going to chart out the topography of that Question, point out some landmarks, draw a few boundaries. And we’re going to equip you with some habits of reflection specifically suited for engaging this most consequential (and slippery) of questions, so that whenever it comes for you, you’ll have the ears to hear it and the resources you need to respond to it well. Think of this as an atlas and a tool kit.

Admittedly, reading this book probably won’t do the dramatic work that a major life experience does. Losing friends to White supremacist violence, encountering a teacher who seems to embody the power and truth of God, suddenly seeing the depth of suffering in the world—these are the kinds of shocks to the system that can’t be planned or predicted or manufactured by a book.

But the Question is unpredictable. When truth and worth are on the table, even a book can lead to serious change. Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) read The Columbian Orator as an enslaved youth and found not only an education in rhetoric but a vision of freedom and human rights. The Question can show up when we least expect it. It lurks behind the seemingly ordinary moments of our lives, ever ready to turn things upside down and put us on surprising new paths.

Maybe all this sounds daunting. Overwhelming, even. Maybe you have a little knot twisting in the pit of your stomach. That’s OK. In fact, it’s good. If all this feels a little above your pay grade, it just means you understand the stakes. The good news is you’re not alone.

Finding Some Friends

The Christian thinker and novelist C. S. Lewis (1898–1963) distinguishes between mere companions and true friends. With our companions, we share some common activity, whether it’s a religion, a profession, an area of study, or just a favorite pastime. This is all well and good, but it is not friendship in Lewis’s sense of the term. Friendship requires something more: a shared question. The one “who agrees with us that some question, little regarded by others, is of great importance,” he says, “can be our Friend. [They] need not agree with us about the answer.”

The Question is too much for each of us to handle on our own. We need friends who will pursue it with us. So here’s an invitation: for the purposes of this book, let’s be friends. The Question is of great importance to us. We care deeply about it. And we invite you to do the same. We don’t need to agree on an answer.

Now, one of the great things about friends is that they often introduce you to other people—people who start out as their friends, but over time become your friends too.

Since 2014, the three of us have been teaching a class at Yale College called Life Worth Living. Over the years, more than a dozen colleagues have taught with us and hundreds of students have participated. We gather small groups of fifteen or so students around seminar tables, and we devote our time together to the Question. For each class, we read texts by a handful of people from major religious and philosophical traditions to help us orient our conversation. We’ve facilitated similar conversations with groups of mid- and late-career adults and a group of men incarcerated in a federal prison. In each context, we treat Life Worth Living as one long conversation among present-day friends, with help from extraordinarily insightful friends from the past.

That’s what we’ll do in the coming pages. As opportunity arises, we’ll bring to the table some of the people from across the globe and throughout history who have thought deeply about the Question. We’ll let them speak up, and we’ll see what they can teach us about what matters most and why.

We’ll hear from the Buddha again and from other major figures from religious and philosophical traditions (Abraham, Confucius, Jesus, and the like), but also from some lesser-known people who followed one of these traditions, and even from some of our contemporaries. Think of this book as a seminar table that breaks the rules of time and space. And somehow we’ve all gotten a seat with the whiz kids. As we tell our Yale students, the more focus you put into listening to what your friends around the table say, the more you’ll get out of the experience.

Before we move on, let’s make four quick caveats. Otherwise, the seminar table approach might lead to some rather serious misunderstandings.

- Most of the time in this book, we’ll be describing what other people think. When we do that, we’ll try to do it well. We’ll try to make those perspectives as convincing as we can. But they won’t be our Not everything we say here is something we ourselves believe. As you read, pay attention to whether we’re representing our own views or describing what someone else thinks. Not only will that cut down on misunderstandings; it will also help you appreciate the dynamic conversation between diverse perspectives that we’re trying to facilitate.

Having said that, it’s important for you to know that we’re not some sort of neutral Good Life tour guides. Nobody ad- dresses the Question from nowhere. We’re all situated and all have our own commitments. So, as we do right off the bat in our classroom, let us tell you briefly where we’re coming from. All three of us are Christians. More specifically, we’re Christian theologians (that means it’s our job to think about Christian faith) who live and work in the United States. We’ve tried our best (for specifically Christian reasons) to be evenhanded in our treatment of all the voices around the table. We’ve tried not to slyly stack the deck. But it would be sneaky not to at least tell you where we’re coming from and let you do what you will with that information.

2. When we bring folks to the table, we’re not supposing that they can speak on behalf of whole religions or philosophical schools. There’s no way to sum up or boil down what is often thousands of years of beautiful tradition in a few Or even a few books. We don’t intend for you to come away from this book thinking that you now understand Confucianism or utilitarianism or Judaism. Instead, we hope you come away thinking you’ve encountered a few key things that particular people in those traditions have said and done. And if one or more of the friends around the table really interest you, go find out more about them. (We say the same thing to our Yale students on the first day of class.)

3. Don’t assume that everyone we’ve brought to the table basically agrees with one another on the really important stuff. It may be tempting to think so, especially for those of us who worry that religious and ideological disagreements drive the social, cultural, and political conflicts of our day. A universal core that everyone agrees on seems to offer a way But no such thing exists. Here, the seminar table metaphor is helpful. Humanities teachers don’t go into their classrooms assuming that the students all already think the same thing. Or that they’ll think the same thing at the end of the class, for that matter. Enduring disagreement is baked into the format.

4. Also baked into the format of the seminar is that someone will inevitably make the last comment in a given conversation—but that doesn’t mean they’ve decided the It just means class is over. So, too, with our imagined seminar table. Some- body has to go last, but that doesn’t mean they’ve given the best or final answer. Just because we end a chapter with one particular view doesn’t mean it’s the right one, or even the one we think is right.

5. Enough throat-clearing. Let’s get going.

Pre-pos-ter-ous

It just so happens that each of us authors has a daughter. When Ryan’s was six years old, she was learning how to read and had got- ten to the point where she was trying big words. Words like preposterous.

Now, when her little six-year-old eyes looked at preposterous, they saw an unpronounceable, unreadable, effectively never-ending string of letters. Everything in her told her to throw in the towel. Except, when you’re the big person reading The Book with No Pic‑ tures to your little brother, you don’t just give up and hand the book to Dad. This is serious business, after all.

The trick, she learned, is to take that big, scary string of letters and break it down into more manageable pieces: pre-pos-ter-ous. Now, that’s a phonetic mountain you can climb.

The Question, we’ve said, is dauntingly big. It’s preposterously big. It’s the kind of question that can tempt you to throw in the towel. Except, when you’re the big person responsible for the shape of your life, you can’t just give up and hand your life to somebody else. This is truly serious business.

We’d like to suggest the same trick here that Ryan’s daughter used with preposterous: take the big, scary Question and break it down into at least somewhat more manageable pieces. As with phonics, so with life-shaping reflection about what matters most— more or less. The more manageable pieces in this case aren’t syllables. They’re somewhat smaller, more focused sub-questions that address individual aspects of the one preposterously big Question. This is the approach we’ve taken with our Life Worth Living class. It works. Students come in not knowing how to start asking the Question or even not really knowing there’s a Question to ask. They certainly don’t know how to answer it. They leave with a set of tools that help them go back to it again and again with more confidence and a better chance of coming to some good answers.

We’ll use the same approach here. In each chapter of the book we take on one of the sub-questions. We introduce the particular sub-question, see who raises their hand to offer an answer, and then lay out the stakes of answering in different ways.

What these chapters won’t do is answer the sub-questions for you. That’s your job. While it’s important to have friends alongside you in the quest, when it comes down to it, only you can actually respond to the Question, or even its more manageable sub-questions, for yourself.

Only You

How free are we to shape our lives? And how much responsibility do we have for them?

At the start of the card game war, you are dealt a random hand of cards. So is everyone else at the table. You don’t know what your cards are, and you can’t see the other players’ either. Each player f lips over the top card on their deck. Whoever f lips the highest card takes all the cards that have been f lipped and puts them at the bottom of their deck. If two or more players tie for the highest card, they each f lip another . . . and another . . . and another . . . until one of them shows a higher card.

The game goes on—inexorably, mercilessly—until one player has all the cards.

There are no decisions in war. There’s only a procedure. Any machine that could recognize which cards were higher and lower could play the game just as well as a human. Nobody is responsible for how the game turns out.

At the start of a round of poker, just like in war, you are dealt a random hand of cards. And so is everyone else at the table. You can’t see the other players’ hands. But in this game, you can see your own. As play proceeds, players make bets and cards are turned over for all the players to combine with the cards in their hands. You’re hoping to build the strongest hand of five cards.

There are rules that say which hands are the strongest. And there are rules about how you can respond at each point in the round. There might be limits on how much or how often you can bet. You certainly can’t f lip over other players’ cards. Or reshuffle the deck at random. That sort of thing.

When you play poker, you’re not in complete control. You don’t pick your cards. Or your opponents’ cards. Or how your opponents bet. Or how they respond to your bets. Or the rules of the game. Most of it is out of your control.

Even so, you’re responsible for how you play your hand. You can’t determine the outcome. That always depends on both chance and how other players act. But you’re not uninvolved in the outcome either. How things turn out depends in part on what you do with the situations you’re given. You’re a participant. And you answer for how you participate.

It seems like war and poker stand in stark contrast. In war, you appear to have no choices and no responsibility, whereas in poker you have some constrained choices and some real responsibility. But here’s the thing: even when you play war, you have a certain kind of responsibility. You’re not even partly responsible for the outcome, of course. But you are responsible for how you play. Will you be gracious to the toddler who’s having the time of her life across the table from you? Or will you resent her for dragging you into this deterministic hell? Will you play by the rules? Or will you sneakily change seats to get the better hand while your opponent is getting a snack? (One of us tried this as a four-year-old. It did not work.)

Is life more like poker or more like war? How much maneuvering room do the “rules” of life give us? It’s hard to say. There are serious arguments on both sides. But regardless of where on the poker-to-war spectrum the truth falls, two points are important. First, you have some responsibility for the shape of your life. (The shape of your life includes both your wins and losses and how you play the game.) Second, that responsibility is not unlimited. It’s constrained. You didn’t get to say where you were born. An enormous, stupefyingly complicated world is always shaping the situations you find yourself in. And you don’t get to determine the outcomes. (Elbow grease and pluck won’t guarantee you success. That’s an American fiction. And a harmful one, at that.)

Not even who you are is fully up to you. Everyone goes through things that shape them in ways they wouldn’t want if they’d had the choice. In really important ways, we simply find ourselves being who we are.

You are not an omnipotent dictator. You don’t call all the shots.

That’s clear enough.

But to go back to the first point, you are also not a rock. A rock doesn’t respond if someone picks it up, chisels it a bit, and lays it down as part of a garden path. You do respond, in limited but nevertheless very real ways, to what happens to and around you. You play your hand.

You’re not a hamster either. A hamster does respond if someone picks it up. There might even be a sense in which it decides how to respond. But a hamster can’t ask how it ought to respond. You can. And because you can, you’re responsible for whether or not you do. Even here, there are constraints. Ancient Mayans couldn’t just decide that enlightenment or following Jesus or seeking racial justice was what life is really about, what they should be seeking. Those weren’t even truly thinkable possibilities for them. But the responsibility here is real nonetheless. Just because there’s a normal path to follow doesn’t mean you’re not responsible for whether you follow it or not. Just because there’s a standard vision of the good life for someone like you doesn’t mean you’re not responsible for whether or not you make it your own.

This is the most fundamental form of that constrained responsibility that characterizes your life. It’s the responsibility to discern, as best you can, what kind of life would be truly worth seeking—the responsibility to see the Question and respond to it.

It’s as Bad as You Think It Is (and That’s a Good Thing)

Without a doubt, the most beloved saying of Jesus of Nazareth in our day is “Do not judge, lest you be judged,” not least because some contemporary Christians are distressingly eager to judge others. We recoil at judgment—especially judgment of our whole lives. Our biggest fear when someone judges some part of our lives is that they’re actually judging the whole.

This book claims that our greatest fears are true. Our lives—not just one or another aspect, but the whole of them—are subject to judgment. Who gets to judge and by what standards—these are important questions. We’ll touch on them in the pages that follow.

But we begin with the idea that our lives as a whole can succeed or fail. Some of the things we do and leave undone indicate successes and failures not just in one or another aspect of life, but of our humanity itself.

But this book also claims that it’s actually a good thing that our lives have these sorts of stakes. The meaning and richness of life as we know it and live it, here and now, comes in part from its serious- ness. A championship game means more than an unplanned pickup game because more is on the line. Even more fundamentally, the weight of our lives comes from their irreplaceability. By most accounts, we have only one life to live. By most accounts, there is nothing more precious than life. To succeed or fail with respect to the whole of our lives is the weightiest thing we can do.

Above All an Architect

Albert Speer (1905–1981) was an intelligent young man and a brilliant architect. When Hitler offered him the role of chief architect for the Nazi Party, he was less than thirty years old. He found the offer impossible to pass up. He was, as he put it, “above all an architect.” And Hitler offered him the opportunity to “design buildings the like of which had not been seen for two thousand years. One would have had to be morally very stoical to reject the proposal,” he wrote years later. “But I was not at all like that.”

So he said yes. And then he participated (more than he ever admitted) in some of the most egregious crimes in history. He served the German war effort, made use of slave labor, facilitated the Holocaust. And meanwhile, he did, indeed, design spectacular buildings.

There is a certain greatness to Albert Speer. It lies in the fact that he was “above all an architect.” That singular devotion to his career made him an exceptionally good architect. But that greatness also contains the monstrosity of his life because that same singular devotion also made him an exceptionally bad human being.

It is possible to succeed in our highest aspirations and yet fail as human beings.

Part of the beauty of our humanity is that we are able to ask the Question and to enact responses to it in our lives. This ability makes possible both the goodness and the corruption of our humanity, both the truth and falsity of our lives.

Perhaps very few of us will ever face the kind of catastrophic failure that Speer exemplifies. Perhaps we will not be confronted with the question of whether achieving our personal ambitions is worth collaborating in crimes against humanity. And perhaps we will therefore escape Speer’s dreadful affirmative answer. Or perhaps we will fall short of our humanity simply by not aspiring to anything of particular note. But each of us has to answer for the shape of our lives one way or another. Is it enough to bet that if we fail to live a life worthy of our humanity, the failure will at least be modest? Or might we instead embrace the Question, devote our- selves to answering it as well as we can, and seek to become people who could honestly say not “I was above all an architect” but “I was above all a human being?”

How to Read This Book

We hope you’re convinced that it’s worthwhile to invest serious time and energy in wrestling with the Question. Stakes as high as the shape of our lives call for serious reflection. That said, it’s important to make a distinction: wrestling seriously with the Question is one thing, and doing that through reading, writing, and dedicated reflection time is another. We recognize that not everyone has the opportunity to reflect on the Question in the specific way we’re inviting you to. Systemic inequalities and existing conditions can make it impossible. Most people throughout history have asked what matters and why, what it means to flourish, what kind of life is deeply worth living. And most of them have done so without relying on reading books and writing down their thoughts. Many have done so in the midst of toil and hardship. Millions still do today.

There are also millions of us who are unable to wrestle with the Question cognitively due to intellectual disabilities and other limitations. Indeed, all of us were unable to do so when we were very young. And many of us will see our capacity for this sort of reflection radically transformed by dementia. There is no bigger human question than the Question, but that doesn’t mean you’re only human if you’re able to wrestle with it.

All of this does mean that there’s a certain privilege in the fact that you’re here reading these pages: at this moment you have abilities and opportunities that not everyone has. We encourage you to take this privilege seriously and use it well. Here are some recommendations for how you might do that while reading this book:

- Read the chapters in order. The five parts of the book follow a progression, and the individual chapters build on one another. You’ll likely get the most out of the experience if you follow this path, rather than jumping forward and backward based on which questions interest you the most. We’ve broken the Question down into somewhat more manageable pieces, but that doesn’t mean it’s just a grab bag.

- Find a pace that works for It may be that you’ll benefit from going slowly. But it’s also possible that you’ll find a groove and want to read one chapter after the next in quick succession. Either approach could be great! Our one caution would be that there’s not much to be gained by just racing from start to finish and then leaving it behind. The Question isn’t an item on a to-do list. We can’t just cross it off and move on. So, whatever pace you settle into, give yourself some space to sit with the questions and claims you encounter. There’s no shame in reading a paragraph, a page, or a chapter twice.

- Consider writing as you It will help you engage actively with the questions and voices we’ll be considering. It doesn’t really matter where you write. Write all over the book if you want (unless it’s a library copy, of course). We’d be honored. Academics that we are, we’re big fans of underlining, highlighting, and writing notes in the margins. Or you may want to grab a notebook or journal to have more space to express your thoughts.

- We’ve offered a section at the end of each chapter called “Your” You’ll find prompts and questions there to help you organize your reflection. These provide opportunities for you to work out your own reactions, thoughts, and convictions. But they could also be seeds for enriching conversations with others. Which brings us to another recommendation. . . .

- Talk with people about the thoughts that come up as you The Question is best considered in dialogue, both with people who you agree with and those you don’t. To be clear: the point isn’t to talk about this book. The point is to talk about the questions and ideas (and ultimately ways of living) that the book discusses. That said, it can be truly wonderful to have a consistent community of people reflecting on the same questions for a specific period of time. If that sounds appealing to you, think about forming a book group and meeting (online or in person) for regular conversations. We’ve created some resources for book discussion groups. You can find them at lifeworthlivingbook.com.

- Finally, cut yourself some We’ve emphasized the stakes and weightiness of the Question. Those are real and true, and it’s important to emphasize them because it’s all too easy to miss the Question entirely. But it’s also important not to put too much pressure on ourselves. Reading one book won’t “answer” the Question for us. That’s not what reading this book (or writing it, for that matter) is for. It’s meant instead as part of a lifelong process. (As authors, each of us found that our responses to the Question have been challenged and refined yet again in the process of writing.) We hope this book offers you something more durable than an answer. We hope it helps you get a better understanding of the Question and the sub-questions along the way. If you come away able to ask and wrestle with more precise, richer, and deeper forms of these questions, that’s plenty. The reason it’s enough is that we’re seeking to build habits of reflection together, along with skills and abilities that make the serious work of wrestling with the

Question more doable. Lastly, we hope you come away with some basic raw material that, over time, you might work into a sturdier, more compelling response to the Question. So to reiterate: the goal isn’t to finish thinking about the Question. The truly important thing is to get started. Let’s do that.

Your Turn

We invite you to start this process by taking stock. The questions below will serve as a life inventory of where you stand now—a glimpse of how you’re implicitly responding to the Question as you live your life. Future exercises will refer back to these answers, so feel free to take a bit of time with them. (Fear not. Future exercises will also be shorter!)

As you answer the questions, notice (but don’t judge) what answers immediately come to mind, and what thoughts surface after several minutes of reflection. Write down your observations, ideally in a notebook or journal. They can take the form of notes, keywords and phrases, full sentences, or longer reflections—whatever you find helpful.

To start, check in with yourself. What’s going on with you right now? Ask yourself:

- How is my body?

- What are my dominant emotions?

- What thoughts have been occupying my mind?

Next, take stock of some key aspects of your life: how you invest your time, money, and attention. Maybe even go straight to the sources—flip through your calendar, look through your recent expenses, or scroll through your newsfeed. Consider the following aspects of your life:

- Time

- What is your daily schedule like?

- What events regularly appear on a weekly, monthly, and yearly basis?

- How much time is unscheduled? What time do you give yourself for rest? Social connection? Spiritual practice?

- Money

- What are your largest regular expenses?

- Who do you spend money on?

- What do you splurge on?

- To what sorts of organizations do you donate?

- Attention

- What’s the first thing you listen to, read, or consider when you wake up? What websites do you frequent?

- Which apps on your phone do you use most frequently?

- Whose voices and opinions are most present to you? (Consider newspaper columnists; TV, podcast, or radio hosts; the people you follow on social media.) What are they saying?

- What’s the last thing you listen to, read, or consider before you go to bed?

For each of these, notice without judgment what comes to mind. Write down your observations, large or small, consequential or seemingly insignificant. Simply gather the facts. Now do the same thing for your orienting emotions (how you feel not just right now, but from day to day in the regular course of your life).

- What are your greatest hopes for yourself? For your community? For the world?

- What are your greatest fears?

- What brings you joy?

- What are your sources of peace?

- What memories trigger responses of regret or disappointment? What memories trigger responses of satisfaction or delight?

- What tends to make you feel embarrassed?

OK, now step back. If someone looked at this inventory (not that anyone needs to, unless you want them to) and they tried to summarize your life, how might that person finish the sentence, “Above all, they (i.e., you) were ”?

How would you feel about that answer? How would you want them to finish the sentence?

If there’s a gap there, don’t worry. We’re at the beginning of our journey, and while it might be uncomfortable, admitting a certain degree of “hypocrisy” can be really helpful at this point. The easiest way not to be a hypocrite is to lower your standards to match your life. It takes moral courage to hold on to standards and at the same time admit that we are falling short of them.

If you’re reading this book with a trusted friend or group (our sense is that all the questions we’re tackling are best tackled together in truth-seeking communities), consider sharing what surfaced for you.

Copyright © 2024 by Miroslav Volf, Matthew Croasmun, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Miroslav Volf, Matthew Croasmun, and Ryan McAnnally-Linz teach the most in-demand course in Yale College’s Humanities Program: Life Worth Living. Students describe the course as life changing, and preliminary analyses by an outside researcher show strongly significant effects of the course on students’ sense of meaning in life.

Volf is the Henry B. Wright Professor of Theology at Yale Divinity School and director of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture, and was awarded the 2002 Grawemeyer Award in Religion for Exclusion and Embrace.

Croasmun is the director of the Life Worth Living program at the Yale Center for Faith & Culture, a lecturer in humanities at Yale College, and the faith initiative director at Grace Farms Foundation. He is the author of The Emergence of Sin and Let Me Ask You a Question, as well as a coauthor with Volf of For the Life of the World: Theology That Makes a Difference.

McAnnally-Linz is the associate director of the Yale Center for Faith & Culture. He is a coauthor with Volf of The Home of God and Public Faith in Action, a 2016 Publishers Weekly Best Book in religion, and has written for The Washington Post’s Acts of Faith blog, Sojourners, and The Christian Century.