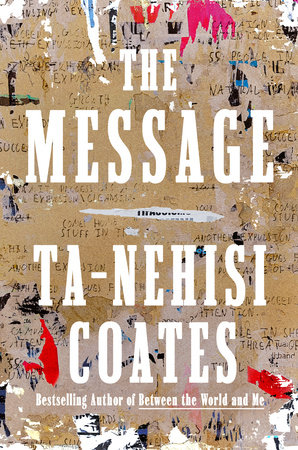

The renowned author of Between the World and Me journeys to three resonant sites of conflict to explore how the stories we tell—and the ones we don’t—shape our realities.

I

Though we do not wholly believe it yet, the interior life is a real life, and the intangible dreams of people have a tangible effect on the world. —James Baldwin

Comrades,

In the summer of 2022, I returned to Howard University to teach writing. Given my rather middling career as a university student, I couldn’t help but feel somewhat sheepish about the honor. But it was an honor, because it was there that I met you. Our first class was in the woods—out in rural Virginia, where, with my friend the poet Eve Ewing, we spent two weeks reading, writing, and workshopping. I’ve been teaching writing in some form or capacity for almost as long as I’ve been a writer, and the only work I love more is writing itself. But with you I found the former rivaling the latter. I don’t mean to slight any other cohort of students I’ve taught in other times and places—all were talented and hardworking. But the fact is, we were drawn together by something more profound.

I guess it begins with our institution, and the fact that it was founded to combat the long shadow of slavery—a shadow that we understood had not yet retreated. This meant that we could never practice writing solely for the craft itself, but must necessarily believe our practice to be in service of that larger emancipatory mandate. This was often alluded to, if not directly stated. All of our work dealt with the kind of small particulars of being human that literature generally deals with. But when you live as we have, among a people whose humanity is ever in doubt, even the small and particular—especially the small and particular—becomes political. For you there be no real distance between writing and politics. And when I saw that in you, I saw myself.

A love of language, of course, is the root of this self. When I was barely six months old, I would crawl over to my father’s speakers when he played the Last Poets. And when the record ended, I would cry until he played it again. At five I would lay on my bed, with the Poems and Rhymes volume of the Childcraft series splayed open to “The Duel,” and all day I could not help but to murmur to myself, “The gingham dog and the calico cat / Side by side on the table sat.” I did this for no other reason than the way the words felt in my mouth and fell on my ears. Later I discovered that there were MCs—human beings seemingly born and reared for the sole purpose of matching the music of language to an MPC snare or 808 kick—and the ensuing alchemy felt as natural to me as a heartbeat:

I haunt if you want, the style I possess

I bless the child, the earth, the gods and bomb the rest

Haunt. You’ve heard me say this word a lot. It is never enough for the reader of your words to be convinced. The goal is to haunt—to have them think about your words before bed, see them manifest in their dreams, tell their partner about them the next morning, to have them grab random people on the street, shake them and say, “Have you read this yet?” That was what I felt whenever I heard Rakim spit, or for that matter the Last Poets. That was the thing that had me murmuring lines from Childcraft. This affliction was enchantment and desire. It was pleasure but also a deep need to understand the mechanics of that pleasure, the math and color behind words, and all the emotions they evoked. I imagine there are children who see a painting and cannot get the image out of their minds. I imagine they turn it over alone at night in the dark, haunted, considering and reconsidering, and a small secret ecstasy grows in them each time they do this, and, just behind this, a need to convey an ecstasy all their own. I was like that from the moment I could inscribe words into memory. And this instinct naturally linked to the world around me, because I lived in a house overflowing with language organized into books, most of them concerned with “the community,” as my mother would put it. And so it was made clear to me that words could haunt not only in form, not only in their rhythm and roundness, but in their content.

When I was seven years old, my mother purchased a copy of Sports Illustrated for me. She taught me to read before I entered school, and encouraged the practice however she could. And what more encouragement could there be than this issue of Sports Illustrated, which featured my hero, Tony Dorsett, running back for the Dallas Cowboys. This was 1983, an era of American football when running backs seemed as large as champions pulled out of Greek myth. How could a man of Earl Campbell’s might move so fast, racing past one defender and then staving in the chest of another? How could Eric Dickerson run so high, against all convention, bounding through holes in the defense, an obvious target that was never caught? These days I will occasionally watch an old clip of Roger Craig, through will alone, breaking off a forty-six-yard run against the Rams or Marcus Allen reversing field in the Super Bowl. But back then, in an unwired world, stories, words, histories—none of it could be gotten on demand. If you bore witness to such a feat—as I did with Allen—it lived in memory until the broadcast gods decided you could see it again. And so a magazine featuring the exploits of one of these heroes was not just, to me, an assembly of words and stories. It was a treasure.

Because I really did believe that Tony Dorsett was magic. He was five foot eight, built ordinary as one of my uncles. But when he slid the lone-starred helmet over his head, he transformed into something untouchable. I remember him darting through the defense, shifting direction at full speed, dancing, sprinting the length of the field, and outrunning an entire team. But whatever my affinity for Dorsett, this is not what I remember about that issue. In fact, until a few months ago, I’d forgotten that Dorsett was even on the cover at all, because deeper in the magazine, I found a story so unsettling, so horrific even, that it blotted out every adjacent detail.

The story was titled “Where Am I? It Has to Be a Bad Dream.” Its subject was Darryl Stingley, who’d once been a wide receiver. I thought of wide receivers as mythical too—contortionists like Wes Chandler, extending back to snag a ball bouncing off into the ether, or acrobats like Lynn Swann, dancing in the air. I absorbed these exploits on Sunday mornings through highlights curated by the NFL itself. But a magazine like Sports Illustrated existed beyond the garden, out in the street where journalism and literature collided. And out there was neither magic nor myth—only the realest of monsters.

And so I read the true story of Stingley, who back in 1978 took a hit on a slant route and woke up in a hospital. The story began there, in the hospital—with Stingley unable to move a single limb, unable to call to his mother or wipe the tears running down his face. In an instant, the contortionist had been rendered quadriplegic. Only a few paragraphs in, I wanted to put the magazine down forever, to escape the story, but I was held fast by forces I could not then understand. I knew that there was something different in the storytelling, something in its style, that pulled me toward it with the gravity of a star, until I was there, I was on the field, yelling, pleading with Stingley to watch out for the incoming hit, and then in the hospital, right next to him, helpless to relieve the horror blooming in his eyes as he realized his fate. And then the star became a black hole, and I crossed an event horizon where I was no longer imagining myself there with Stingley, but was Stingley himself, and it was my body pinned to the bed, and the spokes were drilled into my skull, and it was I crying out to a heedless god.

I haunt if you want, the style I possess. And I was haunted—by a style, by language. And, dimly, instinctually, I understood that the only exorcism lay in more words. I went to my father and bombarded him with questions, because that was the kind of child I was, always (to the annoyance of my siblings) asking why. My father’s way of dealing with this was patented and that day he executed the maneuver to perfection. He led me to the back room, where he kept a large collection of books, and pulled one down from the shelf. The book was They Call Me Assassin. It was the memoir of Jack Tatum—the defensive back who’d laid the crushing hit on Stingley.

And so I delved deeper—hoping for some insight into the mindset of a man who had permanently crippled another. I’d like to tell you I found some great revelation here, but the book was mostly filled with stories of Tatum’s only vaguely interesting football career. I recall Tatum writing that the hit on Stingley was unremarkable in its violence. If a reader came, as I did, looking for some profound meditations on a catastrophe, it was not to be found. And so I was left again to grapple on my own—no Google, no Wikipedia, no social network through which to commiserate with others. Just me and this terrible story of an acrobat entombed in his own body playing over and over in the back of my mind.

Copyright © 2024 by Ta-Nehisi Coates. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

© Gabriella Demczuk

Ta-Nehisi Coates is the author of The Beautiful Struggle, We Were Eight Years in Power, The Water Dancer, and Between the World and Me, which won the National Book Award in 2015. He is the recipient of a National Magazine Award and a MacArthur Fellowship. He is currently the Sterling Brown endowed chair at Howard University in the English department.