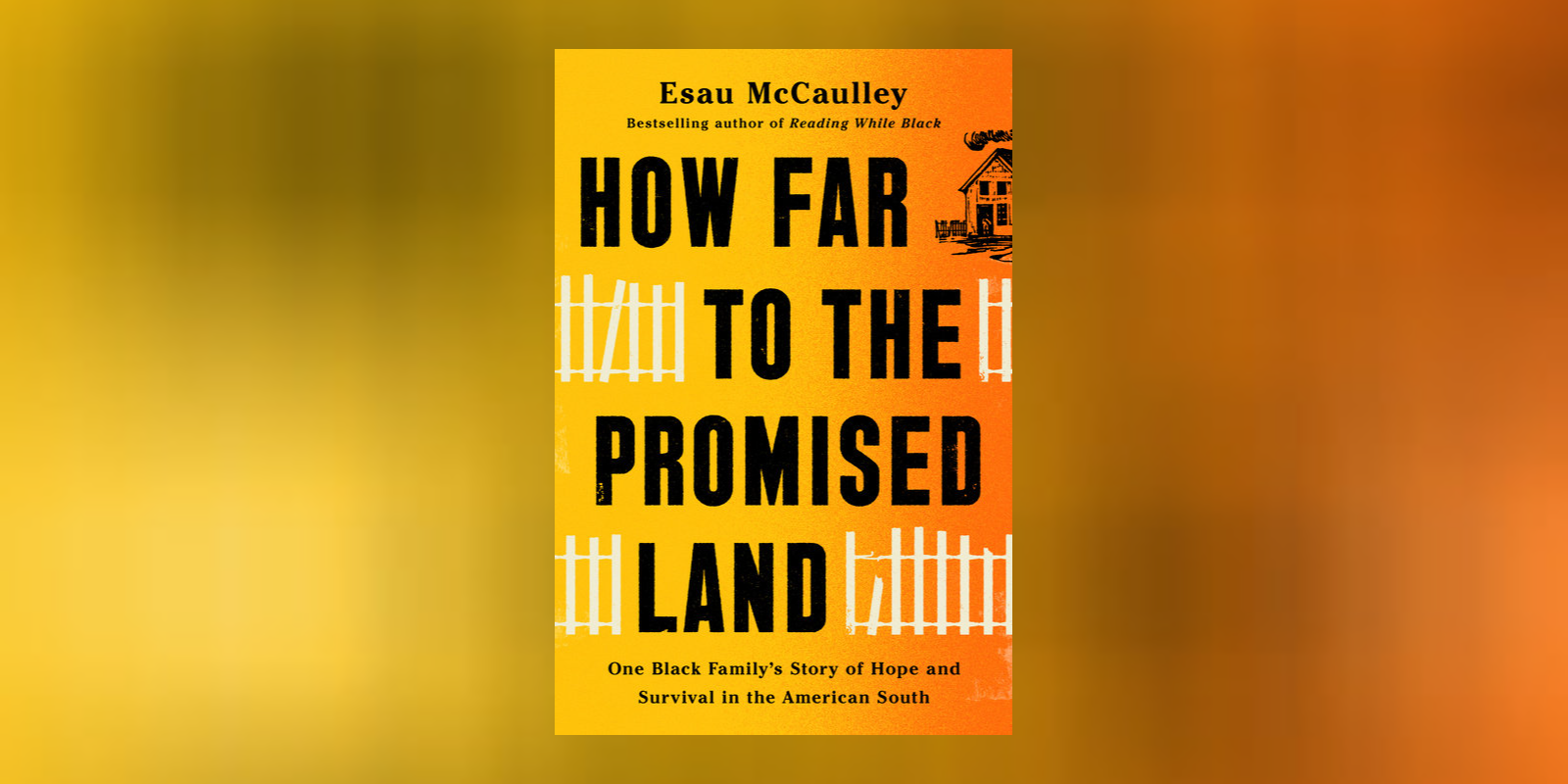

After his father’s death, Esau McCaulley went back through his family history, seeking to understand the community that shaped him: someone who, through hard work, faith, and determination, overcame childhood poverty, anti-Black racism, and an absent father to earn a job as a university professor and a life in the middle class. With profound honesty and compassion, he raises questions that implicate us all: What does each person’s struggle to build a life teach us about what we owe each other? About what it means to be human?

This except from How Far to the Promised Land details McCaulley’s experience arriving as a first-year student at the University of the South.

Chapter 5

Survival Is Complicated

In Huntsville, Blackness had been so normal that I didn’t realize the full impact of living in a Black world until I arrived at Sewanee. I had spent time in the white part of Huntsville, but only as a visitor; it had never been home. There was no “white part” of Sewanee. It encompassed the whole of the campus and the surrounding community.

The coach who recruited me had boasted about the school’s academic rankings. “By the time you graduate,” he’d said, “your brain will be worth almost a quarter of a million dollars.”

Impressed with that figure, I had not considered the cost of the cultural shift.

The University of the South sits on top of the Cumberland Plateau—referred to as “the Mountain” by locals—forty-five minutes outside of Chattanooga; the campus is known for its Gothic-style sandstone and granite buildings. The stately architecture suggested that this place held all that college was meant to provide: a chance to learn and develop while surrounded by splendor. To remind myself of home, I’d brought along my high school football jersey, a collection of CDs, and, at my mom’s insistence, a picture of Black Jesus teaching caramel-colored disciples beside the Sea of Galilee. Because the football players arrived before everyone else, the campus was occupied only by residential staffers, athletes, and international students who lived in the dorms year-round.

Located on the outskirts of the college, my residence hall, a brown limestone building with an open area in the middle, was an inconvenient fifteen-minute walk from the center of campus. From the outside, as I approached, it looked perfect, nestled between a pair of matching lakes, but the concrete interior reminded me of the housing projects I’d visited as a kid, and the walls would remain mostly bare, since damage in the form of nail holes would result in a fine.

I had been assigned a room on the second floor. As I made my way upstairs, the sticky summer heat seemed to follow me, and I noticed that a few doors had been left open by students hoping to catch a breeze; there was no air-conditioning. Balancing a box in my arms, I glanced into a couple of rooms as I passed, then stopped transfixed at a room where a Confederate flag hung from a large section of blank wall. Few images are lodged as deeply in the Black imagination as that blue-and-white X with thirteen stars inside it. Seeing that flag in a place I viewed as an entryway to the land of opportunity caused my body to go stiff and my heart to race. Up to that point, the only Confederate flags I’d seen had been the ones waving from the backs of pickup trucks on Alabama roadways, indicating that I’d taken a wrong turn. This one seemed to suggest the same thing here.

Time slowed as I paused in the doorframe. It was clear that my hallmate had not considered how a Black person might feel upon seeing his flag displayed. When our eyes met, it was not shame I saw on his face but an expression of discomfort mingled with a forced sense of pride. There were no words to bridge the divide between us. That gap widened as I continued my journey down the hall to my room.

That moment would remain with me as a reminder of the fresh trials I would face in Sewanee. Life in Northwest Huntsville had taught me how to survive, to tell by the set of a person’s jaw or the coldness in their eye whether they were a friend or a threat. And my mom’s endless attempts to get me to take schooling seriously had instilled in me a sense of self and dignity. All those lessons had helped me navigate my community and make it to Sewanee, but what about Black life now at a nearly all-white university that still clung to remnants of the Confederacy?

I had arrived at Sewanee on a full scholarship, but I would come to find that many students’ families were able to pay the full tuition, or close to it. Having that much money was so far outside my experience as to be inconceivable. But money wasn’t always evident in how my fellow students dressed; as I’d soon learn, the same people who wore clothes from charity shops drove Rangers Rovers and Lexuses around the Mountain because money meant not having to care about your appearance. The week before spring break, I was sitting around a lunch table with a group of classmates when they asked me about my plans. Since my itinerary didn’t consist of much beyond driving the one hour back to Huntsville, I didn’t elaborate; they then went on to describe their own plans to travel to the Caribbean and Europe. I never quite mastered what to say when people talked of family vacations at ski resorts and summers spent at beach homes. Was I to counter with the memory of my visit to Opryland one year or how I’d considered myself fortunate to partake in a day trip to Six Flags Over Georgia?

And how could we talk about the things that really mattered? Ideological divisions on campus did not run the range from Black pessimism to Black nationalism, from a disengaged Black church to an engaged one, the way they did in my neighborhood. From what I could tell, Sewanee’s spectrum ran from white conservatives to white liberals. The latter wanted the whole of the South to be more like Austin, Texas. They were the ones who had read all the Black books and knew what we needed without actually knowing any Black people. They slid bell hooks and Toni Morrison quotes into normal conversation and complained that Rush Limbaugh had ruined the country. I also sometimes ran into straitlaced conservatives. They told me that I really needed to read Thomas Sowell and learn that the Democratic Party really didn’t care about Black people. All true Christians, I was told, were fiscal conservatives and strict constructivists. Then there were the few blatant racists, who excluded Black students from their social gatherings and wrapped themselves in the lore of the Confederacy. We knew who they were and where they hung out, and we made no real attempt to engage or change them. We and they lived side by side, trying to avoid unnecessary conflicts.

Out-and-out racists aside, my place on the periphery of the school would become most evident to me in the college’s robust fraternity life. Parties took place at a dozen or so frat houses, all of them historically white. Fraternities were a strange mix of people interested in community service, those who wanted an intentional friend group on campus, and folks who threw parties. Different frats had more of one thing or another, but most tended to place a heavy emphasis on having a good time come the weekend. To my knowledge, some had never had a Black pledge.

One of my best friends on campus was a Black first-year football player like me, a guy named Devin. Also like me, he’d grown up in poverty and had never had a relationship with his father. He’d been recruited as a running back; I, a linebacker. Our first day in practice, when the coaches paired us up in tackling drills, he was eager to show his toughness by running over the star defensive player, while I was keen to put the standout runner in his place. I must admit that our battle was pretty even, with him putting a spin move on me in the first rep and me tackling him immediately in the second. It went on that way throughout much of the rest of our time at Sewanee. But competition done with integrity breeds friendship, so Devin and I became close. Two young Black men trying to make it in a white world.

During rush week, Devin and I talked about which frats were most likely to welcome us. First to be crossed off our lists were the fraternities that flew Confederate flags. We went to a few interviews and reconvened to compare notes:

What was it like?

The vibe was off. You know what I mean?

Yes! They said, “We are just trying to determine whether you would be a good fit.” I looked at them and then I looked at myself and wondered what I could say that would make me “fit.” They asked me about my background and interests and how they lined up with the fraternity’s mission. They had all clearly come from money, and nothing in their mission had anything to do with Black people.

In time, the Black students would find each other and coalesce into a community. But I spent most of my first year in my room. Needing to show that I was not some charity case, admitted only because I played football, I stayed up late writing and rewriting papers, determined to prove to myself that these wealthy white students were not better than me.

In my spare time, I initiated protests to revise the university’s admissions procedures, questioning why the student body of thirteen hundred included only some two dozen African American students. Why was there only one Black faculty member in the humanities? I joined with my fellow Black students to push for a more diverse faculty. When I read Cornel West’s Race Matters, I was so moved that I organized a campus-wide event to address racism. I was elected president of the African American Alliance, the Black student group on campus. When Black fraternities refused to establish a chapter at Sewanee, we started our own local fraternity, as a place of refuge and cultural affirmation. My papers hummed with a barely contained fury at the old injustices that I’d read about in books and the fresh ones I experienced as I carried this Black skin into and out of the local grocery stores, restaurants, and gas stations of the tiny towns surrounding the campus.

But in all the fighting and pushing for this right and that new agenda, I lost myself.

Despite my abhorrence for white culture as symbolized by the Confederate flag, I began to adopt a set of white postures and intellectual habits. If my options were Austin, Texas, or the South envisioned by Rush Limbaugh, I chose the former. Austin and I, after all, shared a disdain for the anti-Black policies and habits of extreme conservatism. Yet although we shared a commitment to fight racism, in other ways there were real differences.

Those differences included divergent religious habits. My liberal friends and I often saw God differently. They told me that the faith of my ancestors was an opiate keeping me from liberation. It had been useful in overcoming my childhood environment, but God wasn’t needed anymore. European thought and a sufficiently radical form of democratic socialism would take it from here.

Like the college students I now teach, I adopted the philosophical and political ideas I’d first heard as a freshman and dismissed anyone who didn’t share my newly formed views as lacking enlightenment. I had a good friend on the football team named Chris. He played offensive line and was a bit slow of foot. In practice, I often ran by him or over him on the way to the quarterback. But he handled it all well, and we were friendly on campus. Once, when we were walking out of the cafeteria, he took a risk and asked me if I wanted to go to Bible study. I could see the nervousness in his eyes and his need to be accepted. Even so, I didn’t care. I said, “Nope” and walked away.

It was a small thing, but I remember being pleased with myself for acting so cold and casually dismissive. Forget his feelings, I told myself.

If I’d arrived at Sewanee with the goal of building a résumé that would secure a stable future, it would be difficult to call my first three years anything but successful. I won awards for leadership and intellectual achievements. Graduate school was in my sights if I desired it. Having branched out from my Black social circles, I even tolerated the folk-rockers who filled the fraternity houses on Friday and Saturday nights. I had to admit that a few songs by the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac were passable.

Still, despite all I’d achieved, I couldn’t shake this feeling that might be best summed up with a shoulder shrug. For all my talk of rebellion, I had been formed into exactly what some at Sewanee wanted me to be: a Black intellectual who took the progressive side in all-white conversations about politics and theology. Stated differently, my professors and classmates wanted Black people to call out racism and critique the system, and that was about it. They needed Black voices to challenge their enemies on the right; they needed their critiques dipped in chocolate. That was our role on campus. Even my rebellion felt scripted. I needed to find a distinctively Black and Christian way of being. I needed less Bertrand Russell and more Frederick Douglass. I needed the space to access the unfiltered voices of Black people who came before me.

When I returned home for Christmas my junior year, my aunties and cousins greeted me as the hometown boy who’d escaped and made a name for himself, not knowing that I was mired in internal conflict. Having never been to the Mountain, how could my family understand my doubts about my future and what I was gaining and losing on campus?

In my absence, my former bedroom had been claimed by my younger sister, Marketha, and I was relegated to the room formerly inhabited by her and Latasha. I locked myself in, pulled the drapery closed, and lay across the bed, the rose-petal bedspread and soft yellow walls posing a stark contradiction to my mood. Sleep fled as I listened to the jazz music my grandfather had taught me to love, the various events of the last few years competing for my attention. Something was missing, or maybe everything was missing. All those things that had kept me busy, running from classroom to football field to protest and back again, had served another unseen purpose. They had distracted me from the more pressing question of who I was. Who was the person hiding underneath all the striving? What was I building or becoming other than a series of actions dedicated to a vaguely defined concept of good? I pondered these things as I lay in the dark atop my sister’s bed, listening to Etta James sing that her whole world had gone misty blue.

In that moment, the most piercing of questions imposed itself upon me. It was not a voice but an idea—a question that wrote itself into my soul, a place from which it has never escaped: What do you do when you have everything you ever wanted, but it is not sufficient to bring you joy? An answer etched itself right next to the question, the completion of a thought that arose from elsewhere, more a request than a demand: Consider Jesus. I saw then that all the things that had marked my first three years of college weren’t evil; they simply were not a life. A life needs a telos: a picture of the good, the true, and the beautiful compelling enough to give order to the varied parts of the human experience. The life of Christ had previously captured my imagination, much as it had done for my antebellum ancestors when they gathered covertly, believing God to be the sole hope of the disinherited. At some point during my sojourn at Sewanee, I had set aside that hope passed down to me through the generations. It was time to take it up again, but with nuances born of my time on the Mountain.

Sewanee had given me the intellectual tools to speak about structural racism and the detrimental impact it had on Black life—something that previously I could intuit but hadn’t yet been able to pen into sentences and paragraphs. The university had gifted me with the ability to articulate the overlapping causes of poverty that keep people trapped in the underclass. I was grateful for all that, even if much of that analysis was about my community instead of from my community.

I had been poor, and I had experienced racism. There was another problem missing from the analysis. It wasn’t simply that people out there had done wrong; I had done wrong. I had harmed others, and other poor people had harmed me. The disheveled masses weren’t always noble. We could be as callous as the wealthy.

I didn’t need to be told that society had failed Black people, nor did I need to know that my father had mistreated me. I needed the spiritual resources to forgive or at least to become more than the jumble of grievances I had collected during my twenty-one years on the planet. I didn’t yet have a full understanding of what all this might mean, but that was the beginning of the search for a positive vision of my life that included more than being different from my father.

Copyright © 2023 by Esau McCaulley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Esau McCaulley is associate professor of New Testament at Wheaton College and theologian in residence at Progressive Baptist Church, a historically Black congregation in Chicago. He is the author of the award-winning book Reading While Black and the children’s book Josey Johnson’s Hair and the Holy Spirit. He is a contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. His writings have also appeared in The Atlantic, The Washington Post, and Christianity Today.