In Solito, a young poet tells the inspiring story of his migration from El Salvador to the United States at the age of nine.

Winner of the Los Angeles Times Christopher Isherwood Prize for Autobiography

Winner of the American Library Association Alex Award

Longlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence and the PEN/Open Book Award

Finalist for the PEN/John Kenneth Galbraith Award for Nonfiction

One of the New York Public Library’s Ten Best Books of the Year

Chapter one

La Herradura, El Salvador

March 16, 1999

Trip. My parents started using that word about a year ago—“one day, you’ll take a trip to be with us. Like an adventure. Like the one Simba goes on before he comes home.” Around that same time they sent me Aladdin, Jurassic Park, and The Lion King, alongside a Panasonic VHS player for my eighth birthday.

“Trip,” they say now as I’m talking to them at The Baker’s, where Abuelita Neli, Grandpa, and I go to call them—we don’t have a phone at home, but we do have a color TV, a brand-new fridge, and a fish tank.

“¡Javiercito!” Abuelita Neli waves her hand at me. She’s always called me that. I think my nickname, Chepito, reminds her too much of what the town calls Grandpa: Don Chepe.

“Your parents say you’ll soon be with them,” Abuelita says, and smiles, showing off her two top middle teeth lined in gold. Her dimples dig deeper into her round face. Tía Mali, who also has a round face, isn’t here, because she’s working at the clinic. She and Abuelita have been using the word more and more. Trip this, trip that. Trip trip trip. I can feel the trip in the soles of my feet. I see it in my dreams.

In some dreams I’m Superman, or I’m Goku, flying over fields, rivers, over El Salvador, over all the countries, over the people, towns, all the way to California, to my parents. I ring their bell. They open their huge door, tall and wide, made from the brownest wood, and I run to them. They show me their living room. Their huge TV. Their backyard with a swimming pool, a lawn, fruit trees, a mini soccer field, a white fence. I climb their marañón trees, eat their mangos, play in their garden . . .

Every night, between praying and sleeping, I lie in bed and think about them. ¿What type of bed do they sleep on? ¿Is it big? ¿Is it a waterbed like in the movies? ¿Are the sheets soft? I imagine cuddling right in the middle. The comfiest white sheets. Mom to my left, Dad to my right, a mosquito net like a crown covering all of us.

Whenever a plate breaks, whenever I find an eyelash, whenever I see a shooting star, I wish to be in that bed with both of them in La USA, eating orange sherbet ice cream. I never tell anyone—if I tell anyone my wish it won’t come true.

I have bad dreams también. Bad dreams of growing a beard with my parents still not here. Bad dreams where I’m not up there with them—¡and I’m thirty years old! Bad dreams of being chased by pirates, or running down a hill during a mudslide.

“The bad dreams, those you have to tell first thing in the morning so they don’t stay in your mind. And never in the kitchen, or else they get in your stomach. That’s how you get indigestion,” Mom told me, and I never forgot.

Trip. I’ve started using the word at school. I began telling my closest friends: “Fijáte vos, one day I’m taking a trip. Like a real-real game of hide-and-seek.”

In first grade, I was the only one who didn’t have both parents with me. Mali says they left because before I was born there was a war, and then there were no jobs. Now, most of my friends don’t have their dad or mom here either. A few lucky friends have left to be with their parents in La USA. Most left inside giant planes.

At recess, my friends and I talk about eating our first pepperoni pizza like the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, eating lasagna like Garfield, eating McDonald’s, watching the new Star Wars inside a theater with air-conditioning, eating “popcorn” with butter. I’ve never tried any of these things except for pizza from Pizza Hut, and that was last Christmas.

“¿But will you miss me? ¿Will you?” my friends ask.

“Puesí,” I say, but I don’t really know.

I ask them if they will miss me. “Absolutely,” they say, because no one who’s left to La USA has ever come back to visit. Sometimes their grandma or grandpa will walk by on the street and we’ll ask them how So-and-So is, and they respond, “So-and-So says hi”—that’s the closest they come to remembering us. “Oh, gracias, doña, gracias, don. Tell them we say hi.” But we never hear from them again.

The Baker is still here. His wife and all six of his kids también. They look happy. I want what The Baker’s family has: everyone in the same room. All my friends and I want to be with our parents, where everything is new, fresh, where garbage is collected by trucks, where water comes out of silver faucets, where it snows the whitest snow, where people have snowball fights and cut real pine trees for Christmas—not spray-paint cotton branches in white like we do here.

It’s because our parents are not here and we’re not there that Mays and Junes are sad. For most of us, our grandparents are the ones who show up for Mother’s and Father’s Day assemblies. It’s not that we don’t love them. We do. I love Abuelita so much. I love her cooking. The way my face gets stuck in her curly, frizzy hair that she dyes black, her short hair that makes her look like a microphone, her hair that smells like pupusas when she hugs me. I love her two dimples when she smiles. Her wide and flat nose with its dark-brown mole in the middle that she has to check at the hospital every year to see it doesn’t get too big. And I love her fake eyebrows she draws thin with a pencil first thing in the morning.

I love my mom, también. I’ve never met my dad—or I have, but I don’t remember him. I was about to turn two when he left. He sounds nice over the phone. His voice is deep and raspy, but it’s still soft, like a sharp stone skipping over water. I always talk to him second, after I talk to Mom. I remember everything about her. Her harsh voice like a wave crashing when she got mad at me. Her breath like freshly cut cucumbers.

Now I talk to her first, and then she hands the phone to Dad. Sometimes I’m so shy with Dad, Mom has to be on the phone at the same time. Other times Tía Mali whispers things I’ve done that week to tell him.

They send pictures every few months, and in the pictures Dad looks kind and strong. I like his thick mustache. His thick black hair. His big teeth. The gold chain he wears over his shirt, his muscles showing. Everyone in town tells me stories about him, but I haven’t really asked him anything because I get shy when I hear his voice.

Now Grandpa is talking to them, trying to whisper something into the phone, trying to make it so I won’t hear. But I do hear. I’ve been listening. My hearing is good. It’s really good. I hear him whisper, “Don Dago,” then something else I can’t make out, then he blurts out, “By Mother’s Day.”

Don Dago is the coyote who took Mom to La USA four years ago. He’s been coming around the house more often. I can put two and two together. I’m my grade’s valedictorian; I get a diploma every year for being the best student.

Mother’s Day. Since kindergarten the nuns have made us embroider handkerchiefs with Feliz Día de la Madre or Feliz Día del Padre in blue or red thread. Every. Single. Year. At least the P’s are easier than M’s. In second grade, my friends and I started writing our grandparents’ names instead. It’s easier.

But this Mother’s Day will be different. ¡This is finally the year I see my parents! This year I will embroider Mom’s name on a handkerchief and deliver it to her—in person.

“He’ll get there before summer. He won’t be cold like you were in the mountains,” Grandpa tries to whisper, like I don’t know they’re talking about me. I hide my happiness, my smile, but it’s hard not to run around The Baker’s living room. Hard not to knock the tables over. Hard not to run the four blocks home. Hard not to run into the clinic where Tía Mali is working. I don’t know if I’ll be able to pretend once she gets off work at six p.m. But I do, I pretend, I walk back at Abuelita’s pace, holding her hand. Clutching it. Squeezing it until both our hands sweat and the sweat says: It’s happening. It’s finally happening.

Copyright © 2022 by Javier Zamora. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

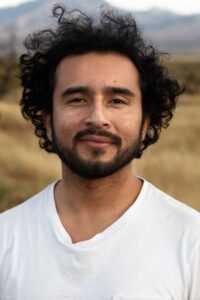

Javier Zamora was born in El Salvador in 1990. His father fled the country when he was one, and his mother when he was about to turn five. Both parents’ migrations were caused by the U.S.-funded Salvadoran Civil War. When he was nine Javier migrated through Guatemala, Mexico, and the Sonoran Desert. His debut poetry collection, Unaccompanied, explores the impact of the war and immigration on his family. Zamora has been a Stegner Fellow at Stanford and a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard and holds fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Poetry Foundation.

Javier Zamora was born in El Salvador in 1990. His father fled the country when he was one, and his mother when he was about to turn five. Both parents’ migrations were caused by the U.S.-funded Salvadoran Civil War. When he was nine Javier migrated through Guatemala, Mexico, and the Sonoran Desert. His debut poetry collection, Unaccompanied, explores the impact of the war and immigration on his family. Zamora has been a Stegner Fellow at Stanford and a Radcliffe Fellow at Harvard and holds fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Poetry Foundation.