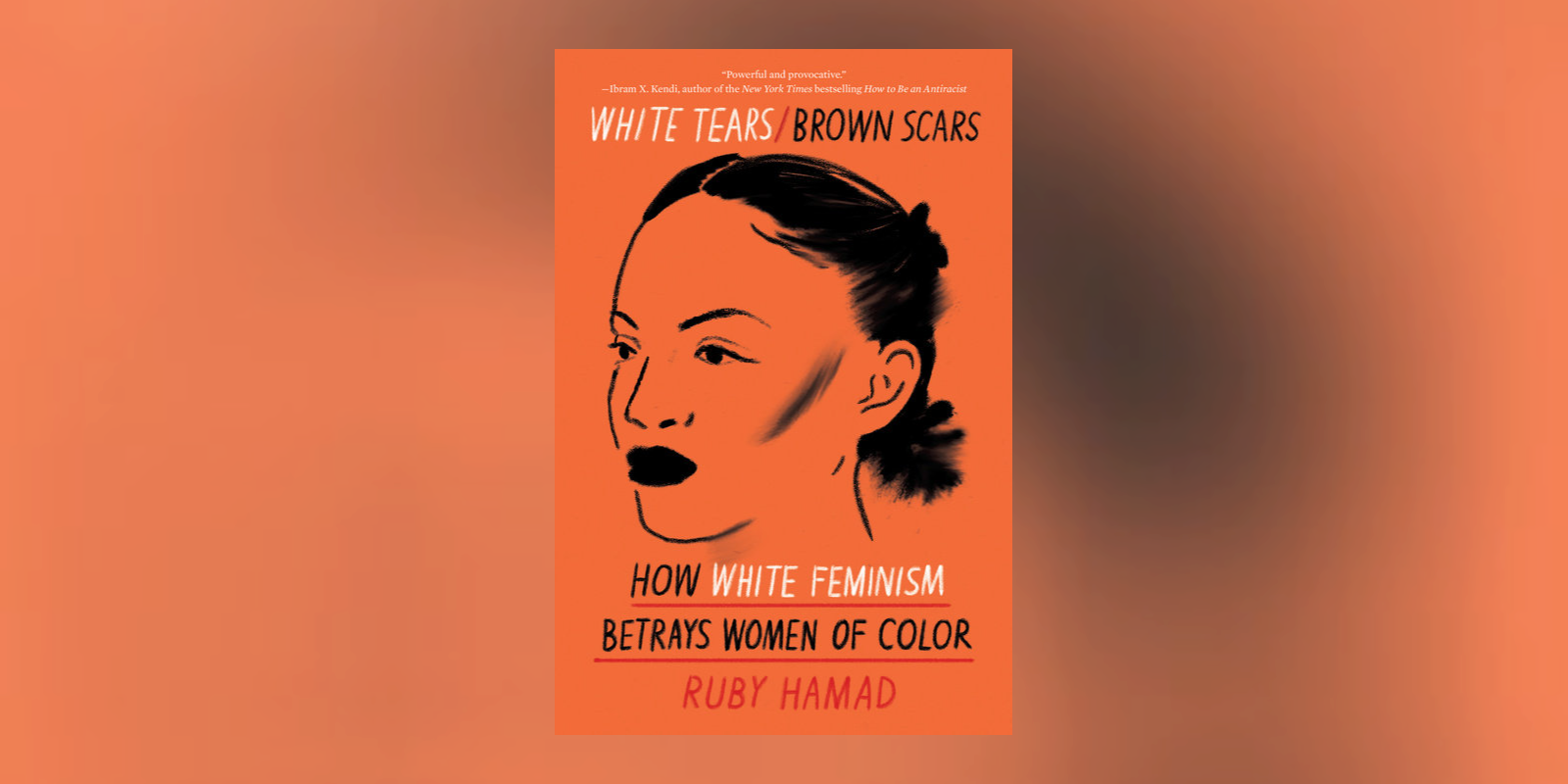

Called “powerful and provocative” by Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, author of the New York Times bestselling How to be an Antiracist, White Tears/Brown Scars reveals how white feminism has been used as a weapon of white supremacy and patriarchy deployed against Black and Indigenous women, and women of color.

Taking us from the slave era, when white women fought in court to keep “ownership” of their slaves, through the centuries of colonialism, when they offered a soft face for brutal tactics, to the modern workplace, White Tears/Brown Scars tells a charged story of white women’s active participation in campaigns of oppression. It offers a long overdue validation of the experiences of women of color.

Discussing subjects as varied as The Hunger Games, Alexandria Ocasio–Cortez, the viral BBQ Becky video, and 19th century lynchings of Mexicans in the American Southwest, Ruby Hamad undertakes a new investigation of gender and race. She shows how the division between innocent white women and racialized, sexualized women of color was created, and why this division is crucial to confront. In the excerpt below, Ruby Hamad explains the conversations, TV shows, and lived experience that inspired her to write White Tears, Brown Scars.

‘I am so uncomfortable having this conversation,’ said Fox News host Melissa Francis during a live broadcast of the network’s panel program Outnumbered on August 16, 2017. The previous day, US president Donald Trump held a press conference denouncing the Charlottesville riots that ended in tragedy when a white supremacist drove his car through a group of people protesting a far-right rally, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer. Trump had audaciously claimed ‘both sides’ were to blame for the violence––and that there were ‘very fine people’ on both sides. This sparked countless debates across the country, much like the one Francis was engaged in with her co-panellists Harris Faulkner, Juan Williams and Marie Harf.

Francis was defending Trump, claiming he was being misrepresented and had never tried to apportion equal blame. When her co-hosts attempted to correct her, she became visibly emotional. ‘I know what is in my heart and I know that I don’t think anyone is different, better or worse based on the colour of their skin,’ her voice cracked. ‘But I feel like there is nothing any of us can say right now without being judged.’ No sooner had the word ‘judged’ left her lips then the tears started. The panel fell into an awkward silence for a moment and it was left to co-host Faulkner, a black woman, to calmly step in and without a trace of emotion in her voice or on her face, to respond. ‘You know Melissa, there have been a lot of tears on our network and across the country and around the world’ Faulkner began quietly but firmly while the other woman closed her eyes and shook her head as if in pain. ‘It’s a difficult place where we are but it’s not where we’ve been, it’s where we are…and we can have this conversation. Oh yes we can.’

What should be remarkable about this clip is that it is the black woman who remains stoic and almost expressionless while the white woman is freely emotional and teary. Keep in mind, this is all in the midst of a conversation about race taking place in the same week that white supremacists had staged rallies waving Nazi and Confederate flags and shouting slogans such as ‘blood and soil’ and ‘Jews will not replace us.’ I say it should be remarkable because, sadly, it is all too unremarkable. It has been so common for so long for people of colour to tiptoe around the feelings of white people that, until relatively recently, it was barely ever commented on in the mainstream. Indeed, after Faulkner’s comments two of the other hosts, including Williams, who is a black man, quickly tried to soothe Francis, repeating how much they hated to see her cry.

How is it that we have been so conditioned to prioritise the emotional comfort of white people? Why does the sight of a white woman crying provoke such placatory responses, even in a context such as this where people of colour have every reason to be scared, upset and even angry? It was not until the following year that I finally began to understand just how crucial it is that we answer these questions.

Fast forward to August 2018, and I almost missed the message in my Twitter inbox from a journalist in the United States asking to speak to me about an article I’d published in Guardian Australia three months earlier. That piece had proved to be very popular and very polarizing and had resulted in far more global attention than I was used to or felt comfortable with, and, still reeling from it all, I assumed she was messaging me to ask if she could interview me for a story. I cautiously agreed to supply my email but was unprepared for what came next.

Lisa Benson, an Emmy-winning African-American television journalist in Kansas City, was writing to me not to request an interview, but to let me know that shortly after my piece had been published in May, she had shared it to her private Facebook page, where two white female colleagues, Christa Dubill and Jessica McMaster, had seen it. The next day, Dubill and McMaster complained to management and Lisa was suspended immediately for ‘creating a hostile working environment based on race and gender’. Shortly thereafter, she was terminated from her contract.

A little backstory: Lisa had already sued her television station employer for racial discrimination, alleging her race was used to determine which stories she was assigned. This includes being sent on her own to interview a Ku Klux Klan member in his home, a situation that was both uncomfortable and possibly unsafe. A separate lawsuit was brought by another colleague of hers, a male African-American sports anchor who claimed he was routinely passed over for promotions in favor of less qualified white men. Lisa was still working for the organization while awaiting her court date, and told me she had shared the article in the hope that her colleagues would understand and empathise with her situation. Instead, it appears they used it as a handy justification for getting rid of a ‘problem’ employee who’d inadvertently broke one of white Western society’s unspoken but most binding rules: don’t challenge or even acknowledge implicit racial bias— if you do, be prepared to suffer the consequences.

Ruby Hamad is a journalist, author, and academic completing a Ph.D. in media studies at UNSW (Australia). Her Guardian article, ‘How White Women Use Strategic Tears to Silence Women of Color,’ became a global flashpoint for discussions of white feminism and racism and inspired her debut book, White Tears/Brown Scars, which has received critical acclaim in her home country of Australia. Her writing has also featured in Prospect Magazine, The New Arab, and more. She splits her time between Sydney and New York.