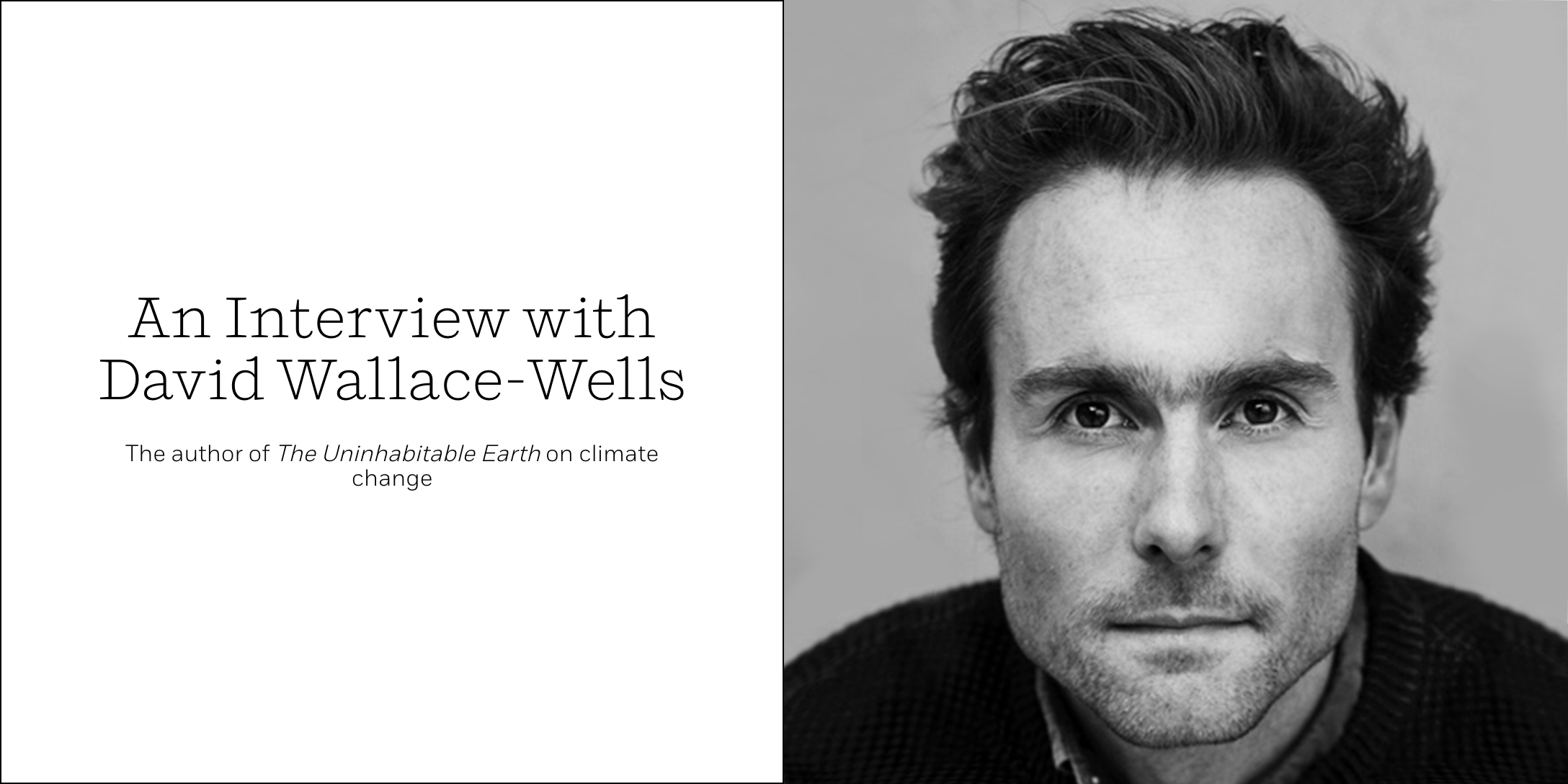

The Uninhabitable Earth by David Wallace-Wells was an instant bestseller when it was published in 2019, and its messages about the threat of global warming have only become more relevant in the proceeding two years. In this video, the author looks at possible side-effects of our changing climate, and offers hope for what we can do to mitigate the crisis.

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT:

Today, the planet is just 1.1 degrees warmer than it was before the Industrial Revolution, and that doesn’t sound like very much, but it means we are already entirely outside the window of human temperatures that enclosed all of human history. The rise of agriculture, and through agriculture, of rudimentary civilization, and through that, of modern civilization—all of that is the result of climate conditions which we have already left behind. Which means, whatever you think is a permanent, lasting, eternal feature of human life—all of it will be affected by climate change.

FOOD

We could lose probably 50% of our agricultural yields just by temperature increases alone, and in fact, scientists warn that as the world gets warmer, it’s not going to be just, say, the croplands in the Midwest that fail. It’s not going to be in the Mediterranean, the parts of China where we grow wheat that are going to fail. There’s an increased risk that all of them will fail at the same time, which means that we won’t be able to simply import the excess crops that are produced elsewhere in the world, because the entire production that year will have been at least degraded, if not absolutely wiped out.

WATER

In many parts of the world, we rely on glaciers for fresh water. Those glaciers are melting, and as that water runs off it gets mixed with salt water and becomes therefore unusable. It’s also the case that in parts of the world, you see a real disappearance of fresh water on the surface. Places like lakes and ponds have that water evaporated and transmitted, and in addition to all that, we’ve begun to extract from underground water supplies that took many millions of years to build up. These are called aquifers, and while there is a lot of water down there, we can’t use it up indefinitely. And because of this water scarcity, we’re likely to see considerably more conflict within nations and between nations.

CLIMATE CONFLICT

We’re likely to see conflicts over productive agricultural land. We’re likely to see conflicts over residential areas that are relatively more habitable, which may test the ability of our political and geopolitical systems to absorb newcomers. You know, if half of Bangladesh is underwater by 2050 or 2075, it’s not like their neighbors in India next door are all that friendly to those Bangladeshis. And there are similar conflicts almost everywhere you look. Now, how the global political system responds to these crises is very much an open question.

WHAT WE CAN DO

Individuals can make changes in their own lives, can reduce their own footprints, but the kind of changes we need to stabilize the planet’s climate are changes of such a large scale they can only be achieved through public policy, which means ultimately for me, I think it really requires political action primarily. Because if 50 years from now, we’re only emitting 10% of the carbon we’re emitting today, we will still be warming the planet further from that point. So if we have a hope of stopping this rolling crisis, it means getting to zero in every aspect of modern life which produces carbon, which is to say, just about every aspect.

Some of the best sociological research suggests that only 3% of a given population needs to engage in protest for the population as a whole to really change its perspective on the issue, and we’re nearing that point with climate.

We have an obligation to get out there and to take aggressive action on climate—action that is commensurate with the scale of the threat as we understand it today.