Dear Readers,

When I first met Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of A Vindication of the Rights of Women, I was 18. She was presented to me in a women’s studies class as a rational, respectable figure: A “proto-feminist” whose revolutionary ideas had included letting women vote (horrors!), get educations (gasp!), and, most controversial of all, study botany (a surprisingly hot-button topic in her time—the plants, you see, were up to all kinds of sexy business, which delicate young girls had best not know). None of this was remotely shocking to me. So, I ignored her.

But in my 20s, I learned that Wollstonecraft had attempted suicide—a bit of trivia that surprised me enough to unearth a book called The Love Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft to Gilbert Imlay. It changed my life.

Wollstonecraft’s letters to her live-in boyfriend/the father of her first child are harrowing. She pleads, she rails, she calls herself “stupid” and wishes for death. She was, to me, suddenly deeply human. Achingly vulnerable. A sexual radical, making her own lonely way in a hostile world. I wondered why my professors hadn’t shown this Wollstonecraft to me—why she’d been hidden for so long.

The answer, it turned out, was that Wollstonecraft’s sex life and suicidal tendencies had virtually destroyed her reputation for a century; that feminism itself may have been delayed by decades because its most vocal advocate was considered crazy and promiscuous.

The phenomenon of the female trainwreck, I realized, is a lot older than the tabloids might have us believe. Charlotte Brontë wrote a “naughty book” about infidelity and was potentially a “fallen woman” herself. French revolutionary Theroigne de Mericourt was passionately feminist before we had the word “feminist,” and her comrades locked her away in a mental institution as the result.

I won’t say that these stories made the women in question more “important,” but it did make them startlingly relevant. They seemed of a piece with the scandalous women of our own age: the Courtneys and Lindsays and Britneys and Whitneys whose sexual choices and emotional “meltdowns” were relentlessly publicized. They seemed like necessary historical background for an age of instant social-media notoriety, where infamy and ruin threaten any woman who makes herself too visible. They offered context for a culture that—in big cities and small towns, in businesses and, yes, on college campuses—polices women’s behavior with extraordinary vigilance.

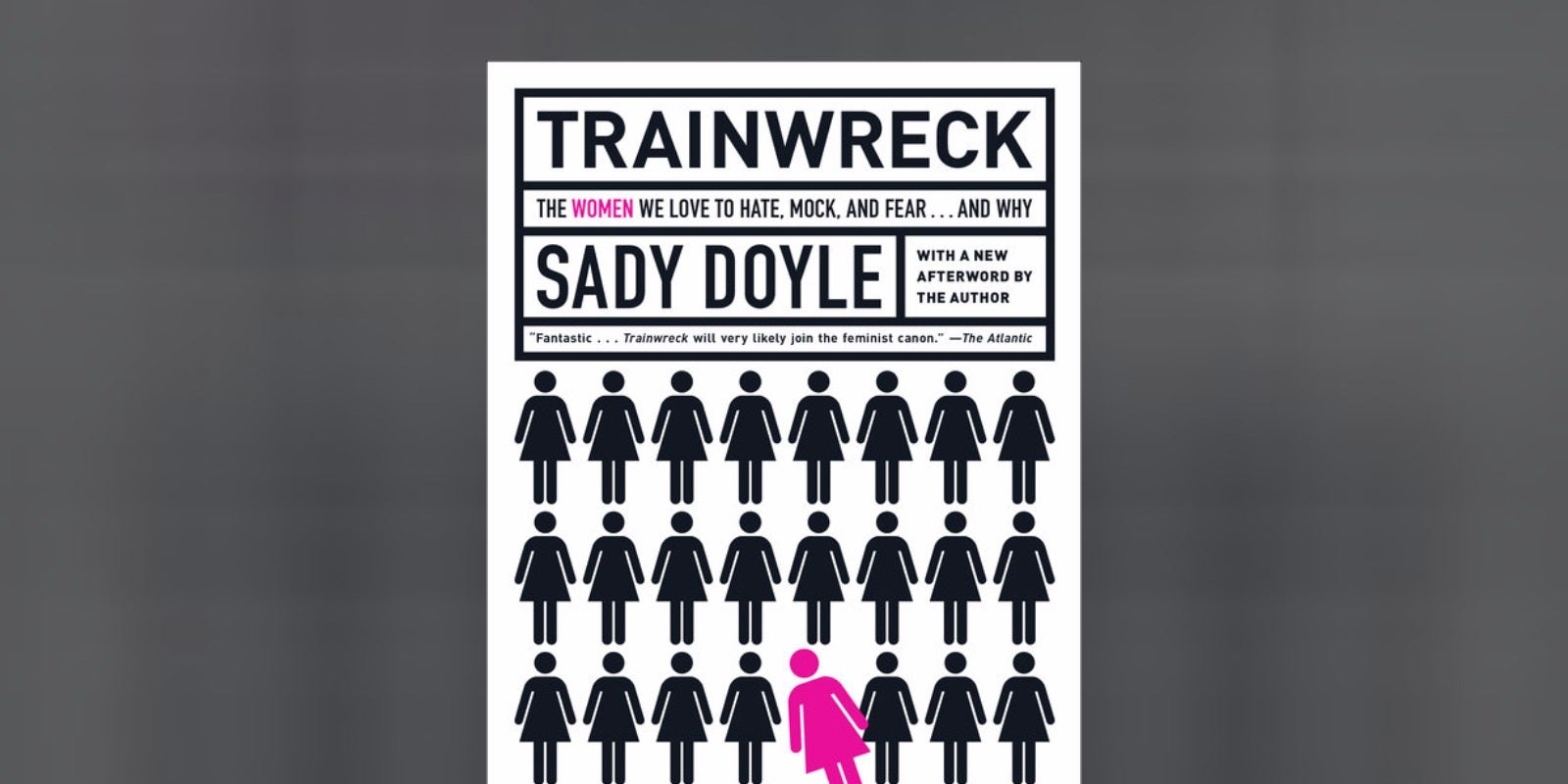

Trainwreck skips up and down the scale of “seriousness,” from Britney Spears to Hillary Clinton, but it does so in the name of connecting both men and women to our own history. I hope you’ll consider it for your students. If I can bring them as close to this history as Wollstonecraft brought me, then maybe some young people will be able to go out into the world with 200 years’ worth of reasons not to be ashamed of themselves.

Best,

Sady Doyle