by Shelley Pearsall

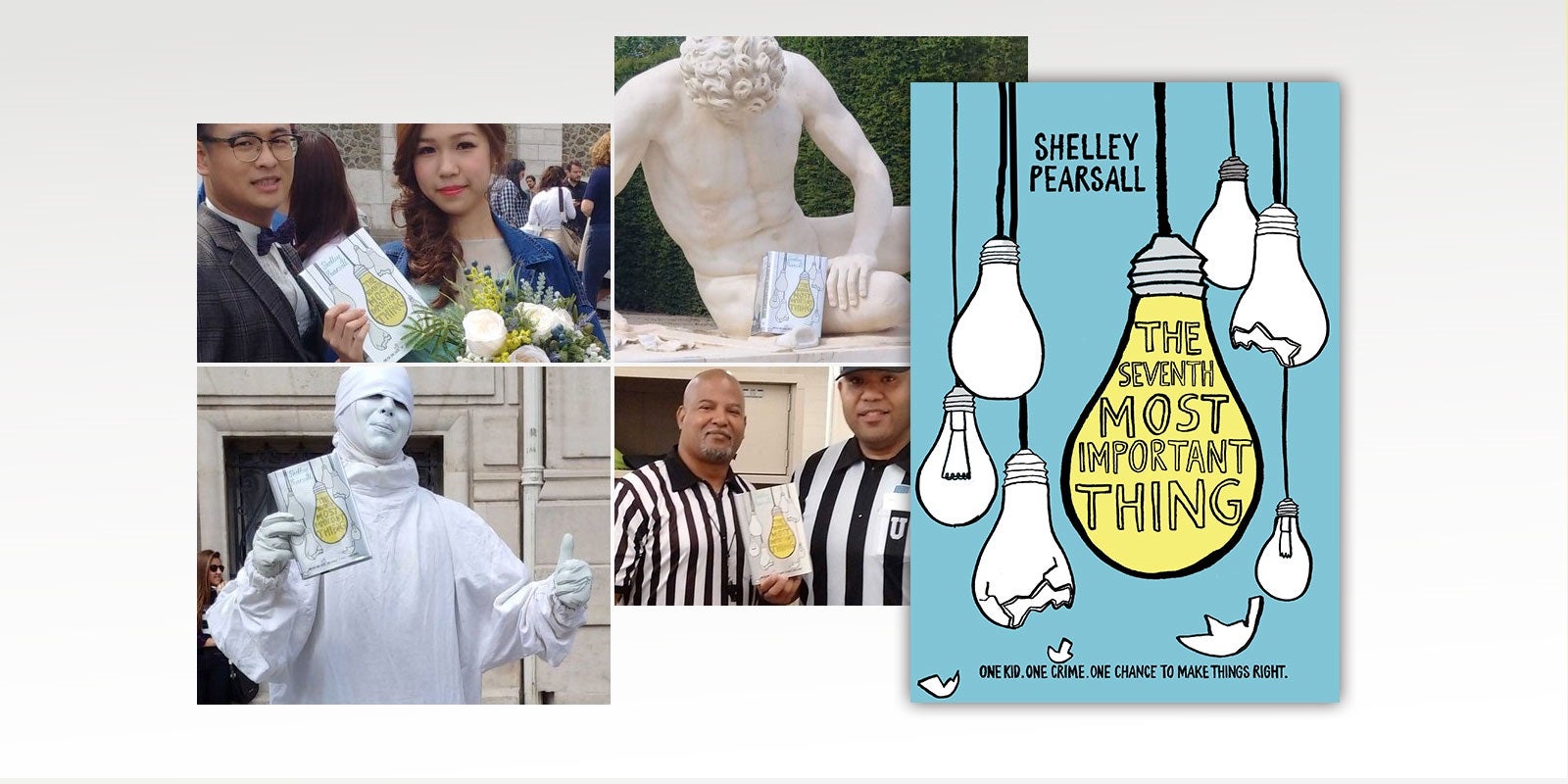

Last summer, my novel The Seventh Most Important Thing went around the globe. It traveled in suitcases and backpacks to Israel, France, Iceland, and England. It sat on a beach. It became part of someone’s wedding photo. It went to football practice.

Mayfield High School, a large suburban high school outside Cleveland, Ohio, wanted to try something different with their summer reading program last year. So they shelved the traditional list of high school summer classics in favor of a single, community-wide choice for all grade levels.

The school chose The Seventh Most Important Thing, typically selected for sixth to ninth graders, because they wanted to encourage entire families to read, discuss—and yes, even vacation with—the book. They hoped to change the way the school community thought about assigned reading, from passive (and often reluctant) to active reading, from SparkNotes to real sparks.

In the novel, a teenager named Arthur Owens is dealing with the sudden loss of his father in a motorcycle accident. In anger, he throws a brick at a helpless trash picker known as the Junk Man. Ultimately, Arthur is sentenced to collect the “seven most important things,” not only for his own redemption, but also for the Junk Man’s secret and spectacular work of art.

The Seventh Most Important Thing touches on many themes—grief, loss, redemption, hope, healing, and the power of art. In other words, there is a lot to talk about. I believe this is one key in choosing a successful community-reads novel: it must touch on universal themes all of us face in our lives to facilitate discussion. I believe that is why this work of realistic fiction is being chosen for community reads.

From coaches to custodians to school secretaries—everybody read. In fact, I often judge the success of a school-wide reading program by one staff person in particular: the custodian.

I can’t tell you how many times a custodian at a school has whispered to me, “You know, I read your book too.” I consider them to be the “book whisperers” of all-school reads because they often motivate and push kids (and other staff members) to read. They frequently serve as the unofficial cheerleaders of the book.

Social media played a big role. Mayfield created a Twitter feed for posting photos with the book. It connected the school community over the summer and kept the conversation going.

One of my favorite parts of Mayfield High School’s reading initiative happened during my visit at the start of the school year. Typically, an author visit means a couple of large assemblies and a small-group lunch with interested writers. However, over the course of three days at Mayfield, I met with a wide variety of groups, including aspiring student journalists, vo-ed nursing candidates, art students, and teachers. In one memorable interaction, a young man with autism shared his concept for a graphic novel with me. The underlying message of the three-day visit was that books and stories are for all of us.

So pack your suitcase and take your school-wide reading choice around the world next summer.

I’ll see you there!