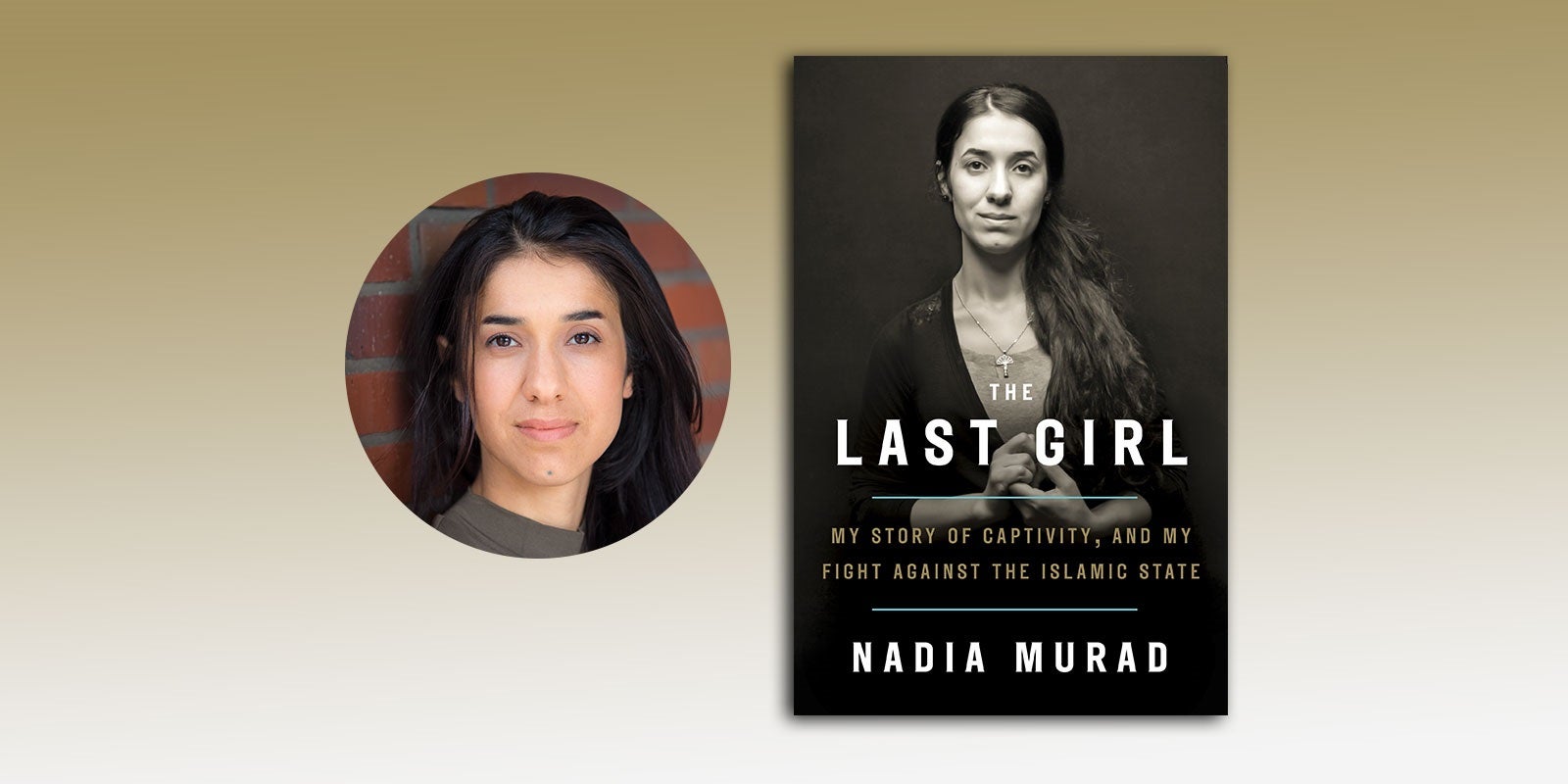

My name is Nadia Murad. I am Yazidi, a member of a small, monotheistic religious community whose holy temples and homelands are located in northern Iraq. Early in the morning of August 3, 2014, militants with the Islamic State attacked Kocho, my small village, and from that moment on my life—as well as the lives of my family, friends, and every Yazidi in the world—would never be the same.

After a siege that lasted nearly two weeks, every villager in Kocho was marched to our school and separated according to age and gender. The men who were old enough to fight the Islamic State were taken behind the school and shot; a handful, including one of my brothers and one of my half brothers, survived. The women were divided according to age and those who were not young enough to be taken into sexual slavery, like my mother, were also killed. I became an Islamic State “sabiyya,” a slave taken during wartime, in Mosul and Hamdaniya. I was raped and beaten, and sold or traded among militants until one day I managed to escape and, with the help of a local Sunni Arab family, make my way to Iraqi Kurdistan and what remained of my family.

ISIS targeted Yazidis because they consider us “kafir,” unbelievers worthy of genocide. They traded women and girls because they thought the Koran gave them permission to do so. Still today, thousands of women remain in ISIS captivity, and those who have escaped or been freed are like ghosts of themselves.

At first I wasn’t sure that I would be able to write The Last Girl. Every time I think about what happened to me I relive it, and the process of writing—searching for detail and trying to analyze it through politics and history—seemed too painful. But since my escape I have devoted my life to telling people my story and explaining to them who Yazidis really are. By writing The Last Girl, I wanted to make people understand what it was like growing up as a member of a tiny religious minority in a country prone to war but in a village steeped in happiness. I wanted readers worldwide to meet my family—those who were killed, like my mother, Shami, and those who, like me, live every day with the memory of what happened to us.

My hope is that after reading The Last Girl people would care enough to act, or at least to tell others: This is what happened to Yazidis in Iraq. It was genocide and it must not happen again.

Over the past three years I have traveled the world and addressed the United Nations, the European Parliament, and countless politicians. But it is at universities where I connect most to the audience. Like me, the students are young enough to feel that no matter how cruel the world is, they are capable of changing it.