1

That fall, across the gold country, it rained steadily, and the people of that hilly land, who lived up and down the spine of the state, looked forward to a season of balanced precipitation. The land, it seemed to them, existed in a state of fragile equilibrium. If there was too much rain, the grasses grew tall, and in the summer when they dried out, they provided extra fuel and triggered large fires. If it rained too little, there was drought, and the land was both thirsty and more prone to ignitions. It had always been like this in the gold country, as long as the oldest of them could remember, but it seemed the margins for error had grown thinner. Anyone who was watching could see this.

So it was particularly concerning when, early that winter, the rains came to an abrupt halt. There were weeks of cold, weeks of wind, weeks of thin overcast cloud cover, but there was never any rain. The wildflowers crisped up along the side of the road and the hills turned brown and the air smelled of dry sage and it was, all of the sudden, the opposite of what many had expected. Had the land ever looked so parched? Had the reservoirs ever run lower? The water districts held meetings, reallocated resources, preached austerity. The fire safety committees updated evacuation plans, scheduled projects of vegetation management. And as May rolled around, and the prospect of any further, significant precipitation came to an end, a waiting game began. Their hand had been dealt. No new cards would be played. The odds were what they were and nothing could be done to change this.

Up on his farm, near the town of Natoma, Benjamin Hecht could not help but feel concerned. Every year, the conditions seemed to be getting worse, the season lasting longer. And yet, worrying about the prospect of a fire helped nothing. So whenever a rush of fear arose, Ben distracted himself with the work of his farm. This was not difficult to do. Over the years, he had amassed a wide variety of projects, which required near constant tending. At present, he had ten new chickens, two dachshunds, honeybees, a small flock of sheep, one guard dog, ducks, geese, several CBD plants, one acre of Primitivo, two of Grenache, two of Barbera, three of Gamay, and three of Syrah. And he had recently acquired, via the guy who ran the concession stand at the Speedway and also bred poultry, two baby emus.

At sixty-five, he was still decently strong, and able to handle the work of the farm. He had a big white bristle of a mustache and, in the last decade, he had developed a slight and inevitable paunch. His wife, Ada, liked to call him “David Crosby without the voice.” The two of them had one child, Yoel, who lived in Los Angeles, and worked in TV development. Yoel was close with Ada, but he no longer spoke to Ben. For years, Ben had tortured himself over the collapse of their relationship, but these days, he had more or less made peace with it. Yoel had his life and Ben had his. That was just the way it was.

In general, Ben felt happy with his lot. Would he have liked more money? Of course. He missed taking Ada out to dinner in town. He would still be taking her out, these days, if she hadn’t told him they needed to cut down on their expenses. He had a hard time reigning in that kind of thing. He got swept up in the emotion of something and forgot about the bigger picture. But he was working on it. Things had been extra tight recently, and they had to find ways to enjoy themselves on a budget.

Ben was particularly looking forward to their annual solstice party. This was a Hechtian tradition, which they had been hosting at their house for nearly two decades now. In June, after Ada sent out an email invitation, the first RSVPs started to trickle in. It was an odd but familiar mix: the Sacramento cousins from Ada’s side, Ada’s old college boyfriend turned family friend and his wife, the Chons, and their neighbors from down the road, the Girouds, who sometimes brought their daughter, and their daughter’s boyfriend, Nick, who had a stone fruit allergy you had to look out for.

The day before the party, Ben woke up around sunrise. He had written the Girouds to double-check, and they had clarified that neither their daughter nor Nick would be joining them. This cleared the way for him to make a peach pie. He also wanted to make a couple of apple pies. Today, he would just deal with the crusts, leave the baking for tomorrow. He put on his old green suspenders and work pants and walked into the kitchen. Once he made coffee and set about gathering his ingredients, he realized they were out of butter. He would need to go to the store. He poured his coffee into a thermos, laced up his boots, and went outside.

The day was already warming up, the sky swirled with a few unambitious clouds. As he walked down the stone pathway to his car, he heard, in the distance, the squawk of one of his chickens. It occurred to him that he should let out the birds before he left. He made his way past the chapel, where they kept the oak barrels of house wine that still needed to be bottled, past the vegetable garden, and down to the coop. It was located on the edge of the property, next to the forest, and it housed their new chickens, as well as their ducks and geese. He’d built the structure almost a decade ago, with his brother, who now lived out on the coast, in Talinas. This was the summer after Ben had been released from Lompoc prison camp. An eighteen-month sentence for growing medical cannabis—one of a few local growers the sheriff had pursued, with the help of the federal government. And it was the same summer, not months after returning home, that he’d started a small, clandestine grow out in the forest. A terrible idea.

Several yards away from the coop, he poured out feed into a few tin troughs. Then he walked back down to the coop, unhitched the door, and released the flock. The birds flipped and flopped and flew toward their food, kicking up dust and dry pine needles in their wake. To the right of their troughs were two blue plastic kiddie pools. He filled them both with water from the hose. Once they had finished eating, the ducks and geese began to hop in, one by one, to take their morning bath. There was some kind of hierarchy in terms of who got to take their bath first. If a willful duck tried to jump the line, they were nipped in the butt, usually by this one brown-feathered goose. He was the smallest goose and evidently had a complex about it. Ben sipped his coffee and watched the animals bathe for a moment before continuing on down the hill, toward the emu pen.

The emus lived nearby the beehives, in a large fenced-in enclosure. They were about three months old, but already nearly three feet tall. As adults, they could grow to be as tall as six feet. When he had first acquired them, he’d tried to put them with the other birds, but this had not gone well. A skirmish ensued and a small white duck had almost been stomped to death. So now he kept the emus down here. They were lanky, mostly-docile creatures, with wrinkled, leathery talons and shaggy gray feathers. As he approached, they grew excited and began sprinting back and forth across the enclosure. They loved to sprint—mostly, Ben felt, to show off how fast they could go. They were a bit vain in this way.

He poured out their feed and watched their heads bob as they ate. When they were finished, he brought the hose over and sprayed it into the pen. The emus began running back and forth across the pen, leaping through the water like kids playing in lawn sprinklers. This was their preferred method of bathing. As he watered the emus, he thought about how he needed to re-jigger the irrigation in the Primitivo blocks and add guano to the CBD in the greenhouse and fix the strap hinge on the door to the sheep pen. He turned off the hose and was about to head up to the greenhouse, when he remembered that the reason he had come outside in the first place was to drive into town for butter. This was the problem with a farm.

—

He made his way back up the hill, past the chickens, who were now pecking around at the brown grass, past the vegetable garden and the chapel, and over to his yellow Toyota truck. Inside the truck it smelled like weed and mountain soil. He started the engine, turned on the air, and tuned the radio to the classical station. From the glove compartment, he pulled out a container of Swedish tobacco. He opened it and placed one of the minty packets between his cheek and his gum. As he backed up across the gravel driveway, he felt the tobacco kick in and, combined with the two cups of coffee, this produced a low-level euphoria.

It was about a fifteen-minute drive into town, on Mountainview Road, through the black oak and blue oak and manzanita, over one-lane bridges and cool mountain streams. Winding down the hill, he occasionally caught a glimpse of the high peaks in the distance, their granite spires and smooth domes. He turned left onto 51, drove past the feed store and the massage and wellness clinic and the old hotel that claimed to have once hosted Mark Twain. Then it was left on Smith Flat Road, past the new brewery and the taqueria, and right onto Center Street.

Natoma was a Gold Rush town, founded by nineteenth century miners, who built Victorian homes along Redbud Creek. Today, its residents were a mix of ranchers, artists, old prospectors, hippies, digital nomads, and retirees. Center Street, the town’s main drag, had more or less been preserved in its historic configuration, and featured a number of businesses, including a crystals shop, several bars, a steakhouse, a used bookstore, a 60-seat movie theater, and a popular cheese store run by a Basque man named Ander. There was also the food co-op, which was where Ben was heading now. It was located in a shopping center just off Center Street, next to the discount liquor store.

When he arrived, the parking lot was jammed. Inside he grabbed a package of butter and then made his way over to the cashiers. Given how many people were at the store, the lines weren’t too bad. The worst one was for under fifteen items. People always got fooled by the under fifteen items line, thought ten people there would go faster than two people with full carts. This was usually, in Ben’s opinion, a miscalculation. He went to one of the shorter lines for people with any number of items.

As he got closer to the front, he realized it was Rudy’s line. Rudy was a very talkative man who had moved here in the late ’70s to prospect and who, over the years, had worked stints at most of the businesses in town. He lived down by the canal with his wife and was always complaining about how there wasn’t enough parking in town anymore. Last fall he had petitioned the city council to build a parking garage. He was sweet, but Ben always found himself caught in conversation with him for longer than was comfortable and he wasn’t in the mood.

He looked over at the other registers to see if he could slip away unnoticed, but their lines had grown long.

“Lot of people in here,” Ben said, when he made it to the front.

“Lot of people,” Rudy said. “My shift’s over soon, thankfully. My daughter and her kids are coming up from Sac this afternoon.”

“Oh, that’s nice,” Ben said.

“You know, I liked your wife’s new book.”

“You read it? That’s great.”

“Yeah, I liked it but I didn’t get why she included that scene at the journalist’s friend’s house. Like, what was the point of that? It was such a long scene. And nothing happened.”

Ben took out his credit card, tapped it on the machine.

“Well, sometimes,” he said, “the scenes where nothing is happening have the most stuff in them.”

He had no idea what he was talking about, was just trying to hurry along the interaction. Rudy ignored his meaningless comment.

“Other than that one part, though,” he said, “I thought it was interesting. Really made me feel like I was in Nevada. I used to live in Fallon for a while. I was in Tonopah too. They have a clown motel there. Anyway, you already know that. It’s in the book. I’m just saying, she got that part of it right, the feel of the place.”

Rudy reached back and snatched the receipt.

“You know,” he said, handing the receipt to Ben, “they’re turning off the power tonight.”

“They are? Is that why there are so many people here?”

“Yeah, probably. Got everything you need?”

“I think so.”

“Because we’re closed tomorrow. Tomorrow’s Sunday.”

“Right,” Ben said. “I’m OK, thanks.”

“Well, let your wife know I liked the book. Tell her I’ll read the next one too.”

Ben walked outside, set his groceries down next to the truck, and took out his phone. He hadn’t turned it on yet. He tried to keep it off while he slept because he didn’t want to get cancer and then sometimes, when he woke up, he forgot to turn it on. There was the notification. The utility company would be cutting power to their area starting around 3:00 p.m. The outage would last for at least a day, possibly longer. It was the second time the utility had threatened to cut power that summer and it wasn’t even July yet. Everything would be OK for the party, though. Ben had a generator at the house and plenty of fuel. He started the car and the classical radio station came back on.

“Up next,” the DJ said, “some memorable music inspired by insects.”

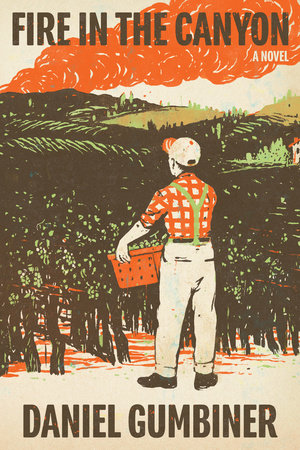

Copyright © 2023 by Daniel Gumbiner. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.