Prologue The Isle of Thanet, November

Late afternoon in November, and it’s dark already. I’m driving. To my left is the sea at Westgate; to my right, the low sweep of Pegwell Bay. Not that I can see either of them in the gloom, but I know this stretch of road well. The land feels spacious when the sea’s nearby, and this is the furthest tip of Kent, the jutting hound’s nose where you’re suddenly surrounded by water.

I’m late. I hate being late. I switch on the radio for company. A man is interviewing a woman. She is talking about the intensity of everything around her; the way all her senses are heightened to light, noise, touch and smell. They make her anxious. I turn on the windscreen wipers and clear myself two arcs in the drizzle. She finds people hard to understand; she would prefer it if they said what they meant.

Too true, I think.

Good luck with that. Then the interviewer says that his son is on the autism spectrum too, and he needs to write everything down or else he won’t be able to take it in, and I think,

Yes but I’m like that, too. I hate plans made on the hoof; I know I won’t remember them. I can’t ever recall names unless I see them in writing. Mind you, I can’t remember faces, either. People just fade in and out of the fog, and I often have no sense of whether or not I’ve met them before. My life consists of a series of clues that I leave in diaries, and address books, and lists, so that I can reorient myself every time I forget.

It’s like that for everyone, though. We’re all just trying to get by. ‘All autistic people suffer from a degree of mind-blindness. Is that true of you?’ asks the interviewer.

‘To some extent,’ says the woman. ‘I’m better at it than when I was young, because I’m more conscious of it as an issue. I’m constantly searching for clues in people’s faces and tone of voice and body language.’

Thank God for my social skills, I think.

Thank God I can get on with anyone. There’s a twinge of discomfort there, as I push away the sense of what that costs me, of how artificial it all feels.

I am good at this, but I have to qualify it with

nowadays.

‘By and large, do you tend to think visually more than you think in language?’ he says.

‘Yes,’ says the woman, ‘I have an eidetic memory.’

I certainly don’t have one of those. Although I suppose I do remember whole pages of books sometimes, like an imprint on my eyelids. At school, my French teacher laughed as I recalled pages of vocabulary: ‘You’re cheating!’ she said. ‘You’re just reading that from the inside of your head.’ And me, at thirteen, squirming in my seat, because I couldn’t work out if this was a compliment – in which case, I should laugh along – or an accusation

.

‘Were you interested in other children, as a child?’ says the man.

‘No, I just didn’t see the point. When I got a bit older, I would try to play with other people, but I wouldn’t get it right. By the time I got to seventeen I had a breakdown, because I couldn’t deal with all the stuff that was going on.’ The memory surges up of those blank days when I thought I might just give up talking for ever, because the words seemed too far away from my mouth; of the red days when I would hit my head against the wall just to see the white percussive flashes it brought; of the sick, strange days when the drugs made everyone else say I was nearly back to my old self again, but I could feel them in my throat, tamping everything down so that it didn’t spew back up . . .

‘One cliché about autism is that romantic relationships are very, very difficult,’ he says. ‘You’re married. How did courtship work for you?’

. . . And I find myself nearly spitting at the radio, saying, out loud, ‘How fucking dare you? We’re not completely repellent, you know . . .’

And that word,

we, takes me quite by surprise.

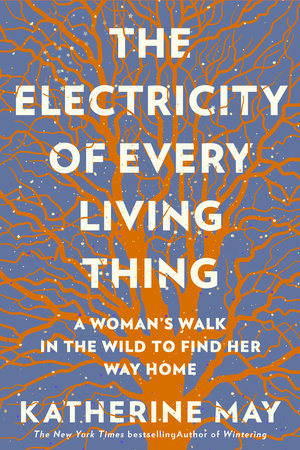

Copyright © 2021 by Katherine May. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.