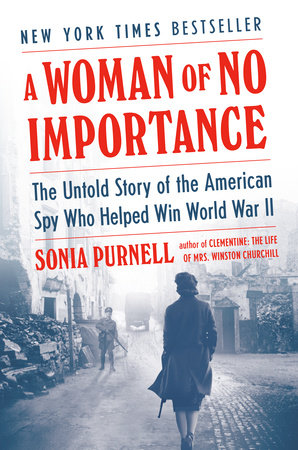

PrologueFrance was falling. Burned‑out cars, once strapped high with treasured possessions, were nosed crazily into ditches. Their beloved cargoes of dolls, clocks, and mirrors lay smashed around them and along mile upon mile of unfriendly road. Their owners, young and old, sprawled across the hot dust, were groaning or already silent. Yet the hordes just kept streaming past them, a never‑ending line of hunger and exhaustion too fearful to stop for days on end.

Ten million women, children, and old men were on the move, all flee‑ ing Hitler’s tanks pouring across the border from the east and the north. Entire cities had uprooted themselves in a futile bid to escape the Nazi blitzkrieg that threatened to engulf them. The fevered talk was of German soldiers stripped to the waist in jubilation at the ease of their conquest. The air was thick with smoke and the stench of the dead. The babies had no milk, and the aged fell where they stood. The horses drawing overladen old farm carts sagged and snarled in their sweat‑drenched agony. The French heat wave of May 1940 was witness to this, the largest refugee exo‑ dus of all time.

Day after day a solitary moving vehicle weaved its way through the crowd with a striking young woman at the wheel. Private Virginia Hall often ran low on fuel and medicines but still pressed on in her French army ambulance toward the advancing enemy. She persevered even when the German Stukas came screaming down to drop 110‑pound bombs onto the convoys all around her, torching the cars and cratering the roads. Even when fighter planes swept over the treetops to machine‑gun the ditches where women and children were trying to take cover from the carnage. Even though French soldiers were deserting their units, abandoning their weapons, and running away, some in their tanks. Even when her left hip was shot with pain from continually pressing down on the clutch with her prosthetic foot.

Now, at the age of thirty‑four, her mission marked a turning point after years of cruel rejection. For her own sake as much as for the casualties she was picking up from the battlefields and ferrying to the hospital, she could not fail again. There were many reasons why she was willingly jeopardizing her life far from home in aid of a foreign country, when millions of others were giving up. Perhaps foremost among them was that it had been so long since she had felt so thrillingly alive. Disgusted at the cowardice of the deserters, she could not understand why they would not continue the fight. But then she had so little to lose. The French still remembered sacrificing a third of their young menfolk to the Great War, and a nation of widows and orphans was in no mood for more bloodshed. Virginia, though, in‑ tended to go on to the end, wherever the battle took her. She was prepared to take whatever risks, face down any dangers. Total war against the Third Reich might perversely offer her one last hope of personal peace.

Yet even this was as nothing compared with what was to come in a life that drew out into a Homeric tale of adventure, action, and seemingly unfathomable courage. Virginia Hall’s service in the France of summer 1940 was merely an apprenticeship for a near suicide mission against the tyranny of the Nazis and their puppets in France. She helped to pioneer a daredevil role of espionage, sabotage, and subversion behind enemy lines in an era when women barely featured in the prism of heroism, when their part in combat was confined to the supportive and palliative. When they were just expected to look nice and act obedient and let the men do the heavy lifting. When disabled women—or men—were confined to staying at home and leading often narrow, unsatisfying lives. The fact that a young woman who had lost her leg in tragic circumstances broke through the tightest constrictions and overcame prejudice and even hostility to help the Allies win the Second World War is astonishing. That a female guerrilla leader of her stature remains so little known to this day is incredible.

Yet that is perhaps how Virginia would have wanted it. She operated in the shadows, and that was where she was happiest. Even to her closest allies in France, she seemed to have no home or family or regiment, merely a burning desire to defeat the Nazis. They knew neither her real name nor her nationality, nor how she had arrived in their midst. Constantly chang‑ ing in looks and demeanor, surfacing without notice across whole swaths of France only to disappear again as suddenly, she remained an enigma throughout the war and in some ways after it too. Even now, tracing her story has involved three solid years of detective work, taking me from the National Archives in London, the Resistance files in Lyon, and the parachute drop zones in the Haute‑Loire, to the judicial dossiers of Paris and even the white marble corridors of CIA headquarters at Langley. My search led me through nine levels of security clearance and into the heart of today’s world of American espionage. I have discussed the pressures of oper‑ ating in enemy territory with a former member of Britain’s Special Forces and ex‑intelligence officers from both sides of the Atlantic. I have tracked down files that were missing, and discovered that others remain mysteri‑ ously lost or unaccounted for. I have spent days drawing diagrams match‑ ing dozens of code names with scores of her missions; months hunting for remaining extracts of those strange “disappeared” papers; years digging out forgotten documents and memoirs. Of course, the best guerrilla leaders do not intend to keep future historians happy by keeping perfect records at five in the morning about their overnight missions, and those that do exist are often patchy or contradictory. Where possible, I have stuck to the version of events as told by the people closest to them. At times, however, it has been as if Virginia and I have been playing our own game of cat and mouse; as if from the grave she remains, as she used to put it, “unwilling to talk” about what she did.

In her secret universe, when virtually the whole of Europe from the North Sea to the Russian frontier was under the Nazi heel, trust was an unaffordable luxury. Mystique was as vital as a concealable Colt pistol. And yet, in an era when the world again seems to be tilting toward division and extremism, her example of comradeship across borders in pursuit of a higher ideal stands out now more than ever.

Nor have governments made it easy to fill in the gaps. Scores of relevant documents are still classified for another generation—although I managed to have a number released to me for this book with the invaluable aid of two former intelligence officers. Still more went up in flames in a devastating fire at the French National Archives in the 1970s, leaving an unfillable hole in the official accounts. Whole batches of papers at the National Ar‑ chives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington, D.C., have apparently been mislaid or possibly misfiled, a handy list of them appar‑ ently overlooked in a move between two buildings. Only 15 percent of the original papers from Special Operations Executive—the British secret ser‑ vice that Virginia worked for from 1941 to 1944—survive. Yet for all these challenges and twists and turns down dark and hidden alleys, Virginia’s story has never once disappointed: in fact, it has repeatedly turned out to be more extraordinary, its characters more vivid, its significance greater than I could have imagined. She helped to change espionage and the views of women in warfare forever—and the course of the fighting in France.

Virginia’s enemies were more deadly, her conduct more daring than many a Hollywood blockbuster fantasy. And yet the swashbuckling tale is true, and Virginia a real‑life hero who kept going even when all seemed lost. The pitiless universe of deception and intrigue that she inhabited might have inspired Ian Fleming to create James Bond, yet she came closer to being the ultimate spy. Eventually every bit as ruthless and wily as the fictional Commander Bond, she also understood the need to blend in and keep her distance from friend and foe alike. Where Bond was known by name to every international baddie, she slipped through her enemies unseen. Where Bond drove a flashy Aston Martin, she traveled by train or tram or, despite her disability, on foot. Where Fleming’s character seemed to rise seamlessly to the top, Virginia had to battle for every inch of recognition and authority. Her struggle made her the figure she became, one who survived, even thrived, in a clandestine life that broke many apparently far more suited to the job. No wonder today’s chief of the British intelligence agency MI6, has revealed that he searches for recruits who do not shout loud and show off but who have had to “fight to get on in life.”

Virginia was a human being with the f laws, fears, and insecurities of the rest of us—perhaps even more—but they helped her understand her enemies. Only once did her instincts let her down, with catastrophic consequences. For the most part, though, she conquered her demons and won the trust, admiration, and ultimately the gratitude of thousands in the process. To meet Virginia was clearly never to forget her. Until the moment she retired in the 1960s from her postwar career in the CIA, she was a woman ahead of her time who has much to say to us now.

Controversy still rages about women fighting alongside men on the front line, but nearly eight decades ago Virginia was already commanding men deep in enemy territory. She experienced six years of the European war in a way that very few other Americans did. She gambled again and again with her own life, not out of a fervent nationalism for her own country, but out of love and respect for the freedoms of another. She blew up bridges and tunnels, and tricked, traded, and, like 007, had a license to kill. What she pursued was a very modern form of warfare based on propa‑ ganda, deceit, and the formation of an enemy within—techniques now increasingly familiar to us all. But her goals were noble: she wanted to protect rather than destroy, to restore liberty rather than remove it. She neither pursued fame or glory nor was she really granted it.

This is not a military account of the battle for France, nor an analysis of the shifting shapes of espionage or the evolving role of Special Forces, although, of course, they weave a rich and dramatic background to Virginia’s tale. This book is rather an attempt to reveal how one woman really did help turn the tide of history. How adversity and rejection and suffering can sometimes turn, in the end, into resolve and ultimately triumph, even against the backdrop of a horrifying conflict that casts its long shadow over the way we live today. How women can step out of the construct of conven‑ tional femininity to defy all the stereotypes, if only they are given the chance. And how the desperate urgencies of war can, perversely, open up opportunities that normal life tragically keeps closed.

Of course, Virginia, who served in British and American secret services, did not work alone. The supporting cast of doctors, prostitutes, farm‑ ers’ wives, teachers, booksellers, and policemen have equally been forgotten but often paid dearly for their valor. Just as what they did for the cause was inspired in part by lofty romance and ideals, so also were they aware that failure or capture meant a lonely and grisly death. Some of the Third Reich’s most venal and terrifying figures were obsessed by Virginia and her networks and strove tirelessly to eliminate her and the whole movement she helped to create. But when the hour of France’s liberation came in 1944, the secret armies she equipped, trained, and sometimes directed defied expectations and helped bring about complete and final victory for the Allies. Even that, though, was not enough for her.

Copyright © 2019 by Sonia Purnell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.