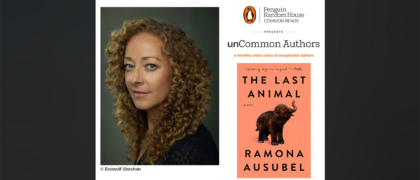

One In the Age of Extinction, two tagalong daughters traveled to the edge of the world with their mother to search the frozen earth for the bones of woolly mammoths.

Eve was fifteen, reshaping herself more each day; Vera, just shy of thirteen, was a stubborn straight line. Jane, their mother, was a graduate student in paleobiology. Their father had died one year before, plunged into a shock-green mountain in a tiny car on a tiny road in Italy where he was doing research for an article. Now they were three. Girls, sad and angry and growing and trying. Mom, sad and angry and trying. Hauling their bodies across the scoop of sky to get to a bare place, a lost place where ancient beasts had once roamed. Somehow, they hoped, this trip would be the beginning of a new road. Gentler, ascending.

* * *

Jane’s professor had grown a beard for the trip to Siberia, and Todd, a postdoc, wore all tan safari clothing. Everything had several pockets and zipped into different configurations. In New York, Vera watched Todd zip off the legs to his pants and jog laps around the terminal in shorts and hiking boots, his stained white athletic socks like burned-down candles. The professor plugged in a full power strip to charge his computer, tablet and two phones and then ate three kale salads out of plastic to-go containers. He said, “We’re unlikely to get fresh veggies. I want to vitamin-load.”

Vera wondered if the professor was someone's father.

During their five-hour layover in Moscow Jane brought blini with caviar on a real plate to the seats where her daughters were draped, sleepy and prickling.

"Airport fish eggs, Mom, I don't know," Vera said. She wanted a burrito.

"You're in junior high, what do you know? They're actually so good," Jane said, sour cream on her lips.

Eve said, "I'm in high school, but I still find this embarrassing."

Todd, in the next row of chairs, again zipped his pant legs off and slung them over his carry-on, then jogged the halls. Eve made a hand flourish and said, "Exhibit A." Vera watched the Russians watch Todd and it seemed possible that he alone might inspire a war between the two countries. Americans, if this was any indication, needed to be put out of their misery. It would have been a service.

As the sun was going down, they boarded a plane that would take them from Moscow to Yakutsk. The stewardesses in stilettos served chicken cutlet and sweet wine. The plane crossed six time zones and they had only traveled two thirds of the way across Russia.

Eve and Vera played a favorite game, Fortunately/Unfortunately, a game that had traveled with them on buses, planes, ships, trains all over the globe.

"Once there were two sisters who wanted to run away," Eve started.

Vera said, "

Fortunately, they had large bags full of precious gems."

"

Unfortunately," Eve continued, "the gems were heavy and the girls couldn't carry them."

"

Fortunately, they came upon a cave where they could hide the bags until they had a way to transport them."

"

Unfortunately, there was a wild and ferocious bear living in the cave."

Vera smiled at her older sister. "You always put a ferocious bear."

"It's a classic."

The story was, by design, endless. Meant to carry the girls across land and sea, every piece of bad news immediately followed by the upswing of salvation.

It was morning again when they landed, dawn a fine pink stripe on the horizon. Vera felt broken by tiredness. She was not a person anymore but a hunger for sleep. The tarmac smelled like fire and melt.

This was the coldest city on earth in winter and all the photos in the hotel lobby were of people with iced eyelashes, men in fur suits with fur hoods selling fish in the outside market and everything shimmered with frost and the fish were frozen but not because they had been in a freezer. It was summer now but Vera could sense the threat of cold.

While the travelers checked in, the professor and Todd had a loud conversation about three-pointers in relationship to wingspan in the NBA. The professor said, "Who wants a drink?" Jane said, "It's morning and I have children."

"Go, go," Vera said. "We will sleep."

"If you sleep now you'll never get onto the right time. You'll ruin the entire trip."

The desk clerk handed Jane her key. It was old-fashioned and had a giant wooden block for a key chain. These were the moments when careers took shape. Trust was earned over jet-lag vodka.

Jane said, "Go walk, girls," and motioned her sleepy daughters outside.

"Alone? In a foreign land?" Eve said.

"It's good for you."

Outside, Eve told Vera, "I've never hated anyone so much in my life." The day cracked at them with its light.

"Dudes, ugh," Vera said, shaking her head.

"Mom abandoned us just now. Don't blame men when it was clearly her choice to make."

Vera said, "She had to. The patriarchy, and stuff?" She looked at her watch as if it could set her right, as if knowing the time would clarify the moment. The watch had belonged to her father, not fancy, a drugstore purchase, but precious because it had been on his wrist and had been a tool for mapping his life. Vera could not get the numbers to make sense.

Everyone on the street was dressed well, especially the women, all looking as if they were about to be photographed. The backdrop was bloc and bland, buildings as storage for lives.

"Americans are such slobs," Vera said. "I am basically wearing jammies and I felt proud that I brushed my teeth and hair sometime yesterday. What are we doing here again?"

Eve said, "That's easy. Mom is pretending to be a necessary part of an important project and not a token woman with both literal and emotional baggage. I can see the headline, Woman, Supposed to Be Invisible, Brings Obnoxious Children on Science Trip, Ruins Everything. Couldn't she have sent us to sleepaway camp? I'd have been a counselor and made out with boys behind the mess hall and gotten in big trouble and learned to paddle a canoe. Instead, this."

Vera said, "We won't ruin anything. Look at us being invisible and out of the way so that the adults can drink vodka in preparation to look for ancient mammoth bits to better understand the genetic code and use that information to edit Asian elephant cells until they act like woolly cells. Plus, tour the future home for de-extincted woolly mammoths. That's a summer well spent."

"Listen to you, little lady. You sound better than Mom."

"I have heard her say that ten thousand times. It's embedded in my brain, like a phone number."

"To making a mammoth," Eve said, holding an invisible glass aloft, toward streetlights strung up on a wire.

They cheered with their fists. "Except I think we're supposed to say 'cold-adapted elephant.'"

Eve said, "How completely lame."

"They don't want to be criticized for playing God."

"You know the professor dreams of snuggling up to a woolly of his own making."

Couples sat on benches and the girls walked across a bridge over a wide, shallow river. The bridge was covered in padlocks. Names were written on the locks. Hearts and arrows and the word "Love" in English.

At the other end of the bridge a worker in a green zip-up jumpsuit cut locks, one by one. He knelt, brought the bolt cutter into place and squeezed. The locks that did not fall into the river were kicked in by the worker, each one sounding a different note as it fell into the water.

Love and declarations of love lasted however long, and then they sank.

"Do you think the grown-ups are drunk yet?" Vera asked. "Drunk enough that we can sneak past the bar and go to sleep?" She looked to her big sister for permission.

Eve said, "All I care about is a bed. I am willing to risk my life for it."

Vera did not know what she was willing to risk her life for. Science, progress, comfort, love, sleep.

The next morning the expeditioners repacked and took their things back to the airport for the last Siberian flight.

The plane had had most of its seats removed to carry cargo. Vera noted cases of rice, beets, a green vegetable she did not recognize. The professor sat atop coolers with pictures of fish on them and Todd perched on a wheel of dark orange cheese. Vera kept waiting for these necessities for survival to collapse under the weight of the American visitors. "Four short hours in blissful comfort," Eve said in plastic-lady voice. "Where are you taking us?" But Jane was bright, visibly excited, and unbothered by her eldest's skepticism.

The region below was more than a million square miles of tundra, permafrost, the earth without human intervention.

Every hour, Todd stood and did a series of stretches, hands raised to the ceiling, his shirt pulled up to reveal a thin strip of pale, furred belly. Eve mouthed, "Ew," to Vera and Vera tried not to picture her hand on that stripe of skin. She did not want to want this crush, and yet . . .

The last airport of the journey was a dirt strip lined with abandoned Soviet propeller planes that looked like a pack of grazing animals.

Thick gray beard and fisherman's hat, a man stood in the dirt beside a yellow car with no front bumper. "Dmitri," he said, squeezing each hand hard. He introduced another man so obviously Dmitri's son that he did not need to state it. "Aleksei," the younger said. Dmitri and the professor hugged and smacked each other's backs. Jane, Eve and Vera were greeted without eye contact. Aleksei took Eve's and Vera's roller bags by the handles and said, "We walk this way."

Vera liked it more than she let on, this faraway feeling, this edge-of-it-all place.

The professor and Dmitri walked together, with Todd and Aleksei behind. Eve and Vera were paired and Jane walked at the back, alone. She looked like the odd kid on a field trip, buddyless. If the girls' father had been alive he would have held Jane's hand as she walked into this mission. Or, if their father had been alive he would have stayed home with the children and Jane would have gone on her own. Either version prickled Vera. This level of parental humanity caused a very specific stomachache. She tried to catch her mother's eye but Jane's attention was toward the horizon.

Vera smelled the river before she saw it. Mud and silt and willows. To reach Dmitri's land on the northern coast of this northern land they would travel the rest of the way on water, a twenty-hour barge ride to the East Siberian Sea. The group had already gone most of the way around the globe yet they had another night and another day before they stopped moving.

The river opened so wide the banks disappeared. It was its own small, moving sea. As they traveled farther, the mosquitoes rose off the water like a living fog and found all the warm skin, this floating feast. The Americans put their jackets on even though it wasn't cold and they wore two pairs of socks and wrapped blankets around their legs and heads, leaving spaces to breathe. Todd zipped the legs to his pants back on and hopped to confuse the insects. The professor wrapped himself tightly in blankets and lay down on the deck like a mummy. If he had died like that no one would have been able to tell the difference. Vera felt like a cocooned creature preparing to be born as a new species. Even outfitted this way, they were bitten. Vera inhaled a mosquito that had found her small air hole. She felt its soft body in her mouth but instead of risking a naked hand to fish it out, she swallowed.

Even Vera, who wanted to be up for the task at hand, now wondered if this had been too much to ask. "I'm sorry," Jane said. She could have come alone. She could have risked missing them. Could have risked them missing her.

There were enough insects that they had weight. If Vera went uncovered she would be bloodless in moments, a sheet of skin.

Dmitri swatted and he said, "You should have seen it a few weeks ago. May is worst. Lucky for you to be here in June."

There was a long sunset in the middle of the night and everything else was noon, and their bodies were so upside-downed that they rested like dogs-someone was always asleep, briefly, then hungry and disoriented. In the dawn or dusk of a day that never ended or began they pulled to a spot on the side of the river where there were two huge posts, and finally, finally tied off.

There was a small wooden dock onto which Aleksei tied the boat. He stood with arms out to help the passengers down. Vera looked out at grass and brush, at the dark wet earth. She could see some small cabins down a path of mud and in the distance were pine trees. It looked like the African savanna crossed with a high meadow. She could hear the river water against the bank and from somewhere, wind or ocean—she was not sure which. Watching the people disembark was a herd of something very big, great hairy bodies and horns. The animals were chewing grass. Todd said, “Compatriots,” and saluted. When Vera stepped out, the ground was spongy and dark. There was a gassy smell, the long-ago seeping out of the earth. Eve and Vera took their own bags this time because Dmitri and Aleksei had boxes of food: coffee, powdered creamer, potatoes, onions, loaves of bread, a gallon of cooking oil, a cooler of moose and a single apple balanced on top.

At home in Berkeley everyone was gluten-free or vegan or lactose-intolerant or avoided nightshades. Even the teenagers ordered cold-pressed green juice instead of coffee (or they ordered coffee but it was single-origin and fair-trade and the cup arrived with a perfect leaf in the organic, grass-fed foam). Dmitri did not ask if there were food sensitivities in the group. These were the available foods and the human bodies required their sustenance.

The large hairy creatures stared at the bald humans. Dmitri said, "Within the park where we have animals grazing the ground is flatter but you should still follow paths. Outside the park you will sink into mud immediately and get stuck. That way is the sea, everywhere else is more and more of Siberia. The size of this land is incomprehensible which is why we need all the animals to help take care of it. You have met musk oxen, we have also bison and wild horses. Grazers to save the world." One animal hoofed at the ground, eyes on Vera, who reached a hand toward her big sister. The thing was ancient and matted and seemed made-up, like a great blanket with legs. Creatures belonged to this place; humans were the obvious intruders.

“

Fortunately,” Eve said to Vera, “the beasts were vegetarians.”

Vera knotted Eve’s fingers in her own. “

Unfortunately, they used their massive horns to defend themselves.”

Eve said, “I’ve always suspected that our parents accepted the probability that we would die in the field.

Fortunately, you won’t be the victim of a mall shooting, but

unfortunately, your mother’s work has now taken you to the land of the angry yak.”

Jane appeared out of nowhere and said, “That’s not a yak, it’s a muskox. You’ll be fine.”

“Dad always told us a nervous vegetarian is more deadly than a hungry carnivore.”

Vera was quiet but a blue pool sat at the bottom of her belly. Her father battered at her. This life of movement and travel and research had been his idea first and he had given it to Jane like a virus and Eve and Vera were born infected. They had grown up on the road, on the move, in countries all over the world. They had been brave, or else they had had no choice. Both felt true, in alternating moments. The summer Vera was nine and Eve eleven their family had been evacuated from Somalia when a civil war had broken out. It was four years ago but Vera remembered perfectly being driven in a bulletproof car through the deserted streets to a grass runway where a small propeller plane waited. It was only them and another white family. Their dad had said, “Life is not easy. You don’t get great art without war. You don’t get progress without cost. You don’t get beauty without suffering.” Only, the person who died wasn’t the one who suffered, Vera now thought. He had been driving too fast on an Italian road but she was the one who had to live with the crash for the rest of her life. A crash that felt like it was always happening somewhere in her own mind. Vera had always wanted to be a good helper and now she bent toward tasks as a matter of survival. Heartbreak paved over with a list of to-dos.

Eve surveyed the high tundra and said, “Dear Diary, I am having the best summer ever! I have made so many fun friends at my life-guarding job and I’m getting a great tan. I think I have a crush on my boss.”

At least there was Eve. At least Eve knew how to be angry out loud. As the firstborn, it was her job to be the icebreaker ship, plowing through her mother’s good intentions. Fifteen was old enough to brew stronger, higher-value anger. Vera’s version, at thirteen, was only a mixer.

“I do not love you,” Eve said to their mother.

“You do love me and I know it. This is exactly, exactly, what love feels like.”

Copyright © 2023 by Ramona Ausubel. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.