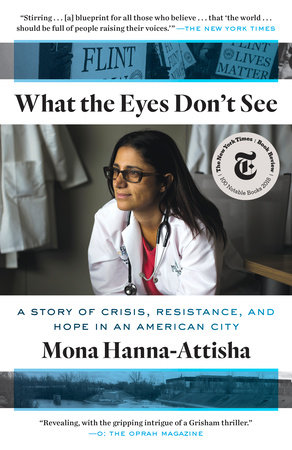

Chapter 1

What the Eyes Don’t See

It was cold and rainy on the summer morning of August 26, 2015—that predictably unpredictable Michigan weather. I dropped my two daughters off at Skull Island, an ominously named summer camp they were trying out for a few days, and got to Hurley later than usual. Once inside, warm, musty air greeted me, that old-hospital smell wafting through the brightly lit corridors of glossy tile.

I reached my office on the pediatrics floor and immediately felt behind the door for my white coat. Wearing the coat always made me feel better, stronger, protected—it was my armor. Then I swung a stethoscope around my neck, completing my transformation from civilian to doctor.

At my desk, I read the local news online for a few minutes—just a quick scan—and noticed another story about the tap water in Flint. Residents were complaining, authorities were explaining. This had been going on for so long, more than a year already. It had become a loop of white noise. Turning my attention to the multicolored grid of my online calendar, I got a handle on the day ahead. It was packed—a crush of meetings, four, five, six of them, for research projects, curriculum changes, faculty recruitment. Somehow, wedged between the meetings, I had to answer emails and read other material, mostly prep for more meetings.

On the home front, a barbecue was beginning to materialize for later that night—a spontaneous, last-minute gathering. I’d discovered that my high school friend Annie Ricci was in town for a few days, and we’d decided to get together with another old friend, Elin Warn (now Betanzo). We had all been friends since our freshman year at Kimball High School in Royal Oak, the inner-ring working-class Detroit suburb where my family had landed after my dad was hired by General Motors. Annie is an opera singer in New York City now. Elin is an environmental engineer who moved back to the Detroit area after many years in D.C. They were both in my wedding, but not as bridesmaids in matching dresses. I didn’t have any of those. Elin and Annie were both serious musicians, so I asked them to perform—and they did.

I reached into the pocket of my white coat for a pen and felt the plastic tip of an otoscope, that pointy tool that doctors use to look inside a child’s ear. The coat may have been my soft cotton armor, but as far as I can tell, the real reason doctors wear white coats is for the pockets. Otherwise there’d be no place to store all our pens, pagers, cellphones, reference cards, tongue depressors, penlights, mints, Chapstick, and otoscope tips.

My fingers felt a scrap of paper, and I pulled it out. The paper was covered in crayon scribbles. A memento. I remembered where it had come from and smiled. Reeva had given it to me. She was a watchful two-year-old who had been coming to our clinic since she was born at Hurley Medical Center.

The week before, Reeva’s four-month-old baby sister, Nakala, had been in the Hurley Children’s Clinic for a routine checkup. One of my pediatric residents, Allison Schnepp, was seeing Nakala; I was the supervising physician. Nakala’s mom, Grace, a young African-American woman with a steady gaze and hair pulled under a loose cap, told us she wanted to stop breastfeeding. I urged her to continue, but she said she’d made up her mind. Breastfeeding took too long and was a hassle—plus, she had to go back to work. She was a waitress, and there was no place to pump in the restaurant except the restroom that all the customers used. She couldn’t afford to do anything that jeopardized her job. As it was, she wasn’t getting enough hours to make ends meet.

She planned to switch to powdered formula mixed with water but had some concerns. “Is the water all right?” she asked, looking skeptical. “I heard things.”

Reeva walked toward me with her hand out. Kids love to distract a doctor who is giving total focus to a younger sibling. So I turned my full attention to Reeva, and she placed the torn scrap of paper in my open hand. She had a sheepish smile, as if she were handing me a secret message, and we shared a conspiratorial look.

“Thank you, Reeva,” I whispered. “I’m going to keep this right here in my pocket.” Then I sat her down on my lap.

The water. I’d been asked about it before.

“Don’t waste your money on bottled water,” I said, nodding at Grace with calm reassurance, the way doctors are taught. “They say it is fine to drink.”

Inches away, Reeva watched me carefully. I smiled at her again, gave her an extra squeeze, and then put her down.

I patted Nakala’s fuzzy little head and touched her fontanel, or soft spot, out of habit, to check its size. It was my chance to explain to Grace that her baby’s skull was open because her brain was still growing. This was the time to stimulate her baby by singing, talking, and reading. Then I gave Grace another nod.

“The tap water is just fine.”

I wanted to be a doctor as far back as I can remember, maybe from obsessively watching M*A*S*H reruns growing up. Or it could’ve been the story about my grandfather Haji that my mom used to tell me, when he fell out of a tree and doctors took care of his broken leg. Or maybe it was the car accident and my early experience with a caring physician who made it seem like everything was going to be okay. My parents are both scientists who raised us to love the multiplication and periodic tables and the majestic order of the natural sciences, so the prospect of biology, chemistry, and math courses never put me off.

In high school, I had some powerful experiences as an environmental activist, so I created an environmental health major at University of Michigan’s School of Natural Resources and Environment, merging environmental science and pre-med courses. My passion for activism, service, and research was solidified there, followed by four years of medical school at Michigan State University; my last two clinical years were in Flint.

It wasn’t a tough call which specialty I’d go into. As a medical student, you have to do rotations in a variety of fields, and as soon as I got to pediatrics, I felt like I was at home. Kids are usually looking for fun, and everything’s new to them. No matter how sick they are, they still want to laugh and play. I was briefly tempted by obstetrics but noticed that as soon as my patients gave birth, I tended to forget about them: my attention suddenly shifted to their newborn babies.

I may not be quite as much of a baby-whisperer as my husband, Elliott, who’s a pediatrician like me but with the supernatural power to soothe any child. I can hold my own, though. With patience and empathy, and sometimes with stickers, bubbles, and penlight tricks, I can get that sulky five-year-old to tell me where it hurts. A nonverbal teenager will talk to me if I take her seriously and listen carefully and let her know that I am her doctor and not her parents’. Even when a baby is wailing and making those supersonic ear-piercing sounds, I know that it just takes a soft voice, a gentle sway, and eye contact to calm them.

A crying baby gives me a sense of mission. Deep inside I have a powerful, almost primal drive to make them feel better, to help them thrive. Most pediatricians do. For some of us, that sense of protectiveness becomes much more powerful when the baby in our care is born into a world that’s stacked against her and her needs aren’t being met—a world where she can’t get a nutritious meal, play outside, or go to a well-functioning school, all of which will diminish her health. I am a fanatic when it comes to protecting all kids, but when I see a child in danger through no fault of her own, I go a little mad. She’s a baby like any other, with wide eyes and a growing brain and vast, bottomless innocence, too innocent to understand the injustice of her circumstances. She can’t see what I can.

A baby who is properly fed and loved and kept healthy, and surrounded by people and communities that value and protect her, has the best chance of becoming a healthy adult. This is what drew me to pediatrics—we pediatricians are at the pivotal intersection of clinical care and prevention. Every aspect of my job—from immunizations to emphasizing the importance of bike helmets—is not just about ensuring kids are healthy today. It’s about tomorrow, next year, and twenty years from now. We see life at its beginning, when it can be shaped for good. As Frederick Douglass said, “It’s easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” Walk into the adult floor of a hospital any day, and you’ll see beds of patients with problems like diabetes or heart disease that can’t be fixed, because to do that you’d have to time-travel back to their childhoods and fix those too.

As much as I love spending time with kids and seeing one little patient at a time, I wanted to have as much impact as I could—on as many lives as I could—so right from the beginning, I made a tactical decision to be a medical educator rather than a pediatrician in private practice. That way, over the course of my career, I could share my passion for children’s health and proven interventions with hundreds of new doctors who would go on to treat thousands of young patients, caring for them as I would and hopefully even better.

And in 2011 I became the director of the pediatric residency program at Hurley Medical Center, a public teaching hospital affiliated with Michigan State University; with more than four hundred beds and almost three thousand employees, it’s a place where new doctors are trained and most of the children in Flint are treated.

The hospital was given to the city of Flint by a soap and sawmill businessman, James J. Hurley, in 1905. And like many public hospitals, it serves a poor and minority population with high levels of Medicare/Medicaid patients and uncompensated charity care. That means budget cuts from the state or federal government hit Hurley hard, in ways they would not hit a private hospital.

When I first took the job in 2011, the pediatric residency program was in tough shape and coming up short in lots of ways, large and small. Morale was low. The sixty-year-old program was at risk of losing accreditation, which meant it could close altogether. Its clinic, where Flint kids came for routine appointments, was in a depressing old building with low ceilings and little sunlight.

The first things I did were to increase the number of our residents and faculty and to overhaul our programs and recruitment practices to attract better trainees. We worked hard to improve residents’ curricula and schedules—and soon we received a full ten-year accreditation. When the lease was up on our old clinic location, we moved our pediatric center into a one-of-a-kind building with soaring ceilings and spectacular sunlight, built above a year-round farmers’ market—and just a few steps from the central bus stop. It was a dream location: the light, the fresh produce, the beauty of the building itself. It was a chance to give the kids of Flint a glimpse at what a healthy environment might look like—but also to show them that they deserved nothing less.

On that August day, we had been in the new Hurley Children’s Clinic for only a few weeks and were still settling in. But I was looking ahead already, to September 15, when applications would come in from next year’s residents.

Recruitment can be difficult when your program is in Flint. Top medical residents want to live in Chicago, San Francisco, Boston, or New York. Luring them to an economically troubled community like Flint takes powers of persuasion, finesse, and assurances that they will be bountifully rewarded, but in ways that are as spiritual and personal as they are practical. But it works. Each year the residents we attract are better, more competitive, and more committed.

So while it’s true that as a residency director, I don’t get to care directly for kids as much as I want, I get to spend most of my days with a group of smart, compassionate young doctors who love kids—and believe in Flint—as much as I do.

Pediatric residency takes three years. Each of those years is divided into four-week rotations called “blocks,” and each block is focused on a different pediatric skill. I direct a rotation called Community Pediatrics, designed specifically to open the eyes of first-year residents to the powerful, but not always immediately apparent, environmental and community factors that affect the lives and health of their patients. There’s an expression I have always liked, a D. H. Lawrence distillation: The eyes don’t see what the mind doesn’t know. The first time I heard that phrase was during my own pediatric residency, when it was uttered by Dr. Ashok Sarniak, a legendary pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Michigan in Detroit. He challenged residents to know every possible disorder or genetic syndrome under the sun and its underlying pathophysiology. When discussing a case and trying to figure out a diagnosis, he watched us run through our limited supply of options, and he always criticized us for not reading enough and therefore not knowing enough, for not seeing the whole picture.

“How can your eyes see something,” he’d say, “that your mind doesn’t know?”

Community Pediatrics is meant to widen the focus of pediatricians beyond whatever is immediately visible. Sure, a nosebleed is a nosebleed. An ear infection is an ear infection. But beyond the common fevers and colds, many children are facing other struggles.

Compared to nationwide averages, Flint families are on the wrong side of every disparity: in life expectancy, infant mortality, asthma, you name it. Flint is a struggling deindustrialized urban center that has seen decades of crisis—disinvestment, unemployment, racism, illiteracy, depopulation, violence, and crumbling schools. Navy SEALs and other special ops medics train in Flint because the city is the country’s best analogue to a remote, war-torn corner of the world.

The city compares badly not just to the rest of the country but to neighboring communities. The median household income is half the Michigan average, and the poverty rate is nearly double. The more adversities a child experiences, the more likely she will grow up to be unhealthy in ways that are completely predictable.

A kid born in Flint will live fifteen years less than a kid born in a neighboring suburb. Fifteen years less. Imagine what fifteen years of life means. In a country riven by inequalities, Flint might be the place where the divide is most striking.

Copyright © 2018 by Mona Hanna-Attisha. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.